Writing in 2000, geographer Michael Dear pointed out the importance of movement in constructing an identity and settlement pattern for Los Angeles. Both literally and metaphorically, the importance of movement in defining LA’s identity remains sacrosanct. Transportation systems seemed to always keep the region in motion while also constantly changing. As Dear points out, architect Reynar Banham suggested the city and its outlying regions were a “transportation palimpsest” or as Dear summarizes a “huge tablet of movement,” always under going change by subsequent generations. If railroads first organized the region, they eventually gave way to streetcars, which then receded in favor of automobiles. Each contributed to settlement and neighborhood patterns, though cars more than the other two lent themselves to the decentralized organization: “Streetcars had facilitated, suburbanization primarily along clearly defined corridors; the car, however, permitted urban development in any area where a road could be cleared.”* Subsequently, “freeway rationality” replaced transit oriented planning, as “freeways ultimately created the signature landscape of modernist Los Angeles – a flat totalization, uniting a fragmented mosaic of polarized neighborhoods segregated by race, ethnicity, and class.”**

Despite Los Angeles’s identification with movement and transportation, in many ways, the west coast metropolis remains a latecomer to such identities. For much longer, New York City has served as a hub for movement: physical, social, economic, and even existentially. Though consisting of five boroughs, Manhattan, the Bronx, and Brooklyn tend to dominate the attentions of the wider public. However, over the course of the past twenty or thirty years, Queens has assumed a new cultural relevance in the popular mind, an identity intertwined with transportation. Physically, Queens serves as the location for two international airports (JFK and LGA), the Long Island Railroad, the Long Island Expressway, significant stretches of the Brooklyn Queens Expressway, numerous subways lines (including the famous 7 train), Airtrain (the light rail service to JFK), and even the “Boulevard of Death,” aka Queens Boulevard (so named because of the numerous fatalities that have unfolded as residents have tried to cross its wide expanses on foot). Additionally, when one considers the numerous livery cab services and taxi dispatchers, Queens appears awash in kinetic energy. This transportation nexus facilitates movement within Queens, throughout the boroughs and region, and even to places abroad.

In a more metaphysical conception, the people of Queens also represent this constant movement. More than any of the five boroughs, Queens remains the borough of immigrants. They come from everywhere, whether it be Koreans/Chinese in Flushing, Poles in Ridgewood, Greeks in Astoria, Pakistanis in Jackson Heights, South Americans and Mexicans in Elmhurst, or any other nationality you might seek, Queens serves as the new Ellis Island, facilitated by the very transportation nexus discussed above. Moreover, the county of Queens itself still tops lists ranking diversity by ethnicity and race. The transportation infrastructure brings new peoples in, enabling not only physical, but also economic and social movement.

Rather than wearing down the borough, their movement refurbishes it. Take, for example, Saskia Sassen’s work The Global City, a seminal study of the role of Tokyo, London, and New York as central nodes in the process of globalization. Sassen concluded that in New York, more so than its counterparts London and Tokyo, immigrants have provided a low level gentrification, repairing neighborhoods and communities abandoned by deindustrialization. For years, housing starts and the like in Queens outpaced the other five boroughs. Additionally, the suburban nature of large swaths of Queens represents the “American Dream” to many, a dream that includes groups that have often been excluded. For example, Queens has the highest rate of black homeownership in the five boroughs. Archie Bunker’s next-door neighbor George Jefferson might be a useful representation here. Strivers only need apply.

Even if one finds the reflections of academics dubious, consider the popular culture examples below.

“Where is the only place a King can find a wife? Queens!” – Coming to America (1988)

Think about the social imaginaries of a borough defined by immigrants defined by transportation. Much of the Queens immigrant population is looking to transport themselves to the middle class/homeownership that has driven housing starts in the NY region for years, while simultaneously gentrifying these neighborhoods (in a way a collective if sometimes divisive form of travel as well). One might even suggest that Queens as the transportation/immigration borough remains defined by, consisting of, and dwelling in world movement. Eddie Murphy’s African Prince, soon to be King, comes to Queens to find a suitable woman for his partner in royalty, landing smack dab in the middle of the borough’s poorer immigrant and black communities, while chasing a woman from its established black middle class. Economic, social, and physical travel all rolled into one.

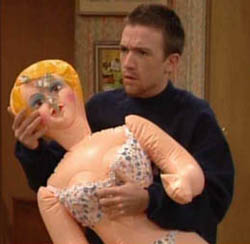

The King of Queens (1998-2007)

A blue collar couple hacking it out in New York’s most residential borough. What does Kevin James’s character do for a living? He’s an “IPS” driver, hoping to move up as he travels throughout the city, transporting goods to all those who so desire them. To this day, Maspeth, Queens houses one of UPS’s main warehouses for delivery, an entire building waiting to be moved. Finally, do not forget UPS ships internationally. Go brown.

A Guide to Recognizing Your Saints (2006)

This small independent film featuring Robert Downey Jr. as Queens resident Dito provides a coming of age story in 1980s Queens. Within the film, his character remains defined by movement. When Dito takes a dog-walking job in Manhattan, his friends look askance (“Why leave Queens?”), representing the tensions of a place based identity in borough where for many place seems ethereal. Moreover, in one of the movie’s pivotal scenes a central character dies when he fails to climb off the subway tracks. Transportation can be one way; sometimes it is not beneficial. When Dito escapes Queens after some harrowing experiences for Los Angeles (from one city of movement to another), it traumatizes not only himself, but also all those around him. Again, travel can be traumatic, especially when the sedentary collide with the transitory.

“I am Queens Boulevard – Vince, Entourage (2007)

When the arguable main character of the HBO series makes this announcement, he was attempting to validate his role in an upcoming movie about the borough. Even as he and his “boys” had settled in Los Angeles (again, LA as the counterpoint to Queens), Vince’s whole persona depends on his Queens attachment. Uniquely, the quote works on several levels. For the audience it seems like an overstatement, self-importance coming through as parody. Within the show itself, it validates both Vince’s commitment to the project and his home; a nifty writing job on a show not always know for such sharpness. Of course, one might ask why one identifies with Queens Boulevard (except that it was the name of the movie he was to star in). Still, Vince a native born American ensconces his identity in a physical example of Queens transportation, one that has received attention in recent years for its more morbid character (see above).

John Rocker – former pitcher Atlanta Braves (1999)

On the 7 train and New York “I would retire first. It's the most hectic, nerve-racking city. Imagine having to take the [Number] 7 train to the ballpark, looking like you're [riding through] Beirut next to some kid with purple hair next to some queer with AIDS right next to some dude who just got out of jail for the fourth time right next to some 20-year-old mom with four kids. It's depressing."

On New York City itself: "The biggest thing I don't like about New York are the foreigners. I'm not a very big fan of foreigners. You can walk an entire block in Times Square and not hear anybody speaking English. Asians and Koreans and Vietnamese and Indians and Russians and Spanish people and everything up there. How the hell did they get in this country?"

While John Rocker may have been a troglodyte, his 1999 remarks represent a perspective shared by significant segments of the US. The idea of traveling on subways with wide swaths of ethnicities, classes, and races, fails to appeal to many Americans. With the current debate on immigration descending into rough calls for American patriotism and Glenn Beckian idiocy, Rocker’s quote represents the fears that transportation can bring. Movement is dynamic, but for some it represents something very scary. Rocker probably has no idea where Beruit is, or the two decade civil war it endured, but this is probably how some people interpret the very movement/transportation Queens enables.

Keep these ideas in mind as you take in Professor’s Cummings work. The tension of being the most residential and transporting borough can bring heartache, tragedy, and anger, but it can also be liberating, inclusive, and joyful. It’s never anyone of these things while at the same times all of them. Perhaps a word or two from the Mountain Goats might help:

“Going to Queens”

the ghostly sing-song

of the children playing double-dutch.

I felt the wind come through the window

I felt it turn around and switch back.

in the second story room in jamaica queens

your hair was dripping wet.

your skin was clean.

and the children skipping rope tripled their speed

you were all I'd ever wanted

you were all I'd ever need.

in new york city

in the middle of july

the air was heavy and wet

the air was heavy,

your body was heavy on mine.

I will know who you are yet.

I will know who you are yet.

* Dear, Michael J. The Postmodern Urban Condition, 107. Notably Dear dismisses streetcar conspiracy theories, instead arguing the ascendance of the automobile resulted from Angelenos distaste for crowded streetcars” … the privacy of the car suited them. This also fits in well with arguments that more than older American cities, Los Angeles celebrates this social privacy.

** Dear, Michael J. The Postmodern Urban Condition, 110.

RR