The Old 321 Flea Market in Dallas, NC is now known as the I-85/321 Flea Market, even though it is even farther from Interstate 85 than it is from Highway 321. The name change is most likely designed to lure the bargain hunters who seek out flea markets to come to the small town of Dallas by suggesting that the market is right off the interstate, when it is actually situated in a semi-rural stretch of town on the way to the even tinier hamlet of High Shoals.

But the name change also reflects the greater connection of Dallas and Gaston County in general to the broader world, as symbolized by the interstate that connects the area's mill villages to a more cosmopolitan circuit of commerce and culture from Atlanta to Raleigh, with the all the migration that the transportation infrastructure brings. Gaston is part of the larger Charlotte-Concord-Rock Hill metropolitan statistical area with an estimated 2009 population of 1,745,524, a large increase of the 2000 census tally of 1,330,448. Up until the 2008 financial crash, the economic prosperity of the greater Charlotte region brought not only migrants from dying industrial areas in the Northeast and Midwest but also a vast number of immigrants from beyond the borders of the United States. Gastonia itself witnessed an 8.2% population growth rate between 2000 and 2010, and large numbers of new Latino, Asian, African and other migrants contributed to these totals.

But the name change also reflects the greater connection of Dallas and Gaston County in general to the broader world, as symbolized by the interstate that connects the area's mill villages to a more cosmopolitan circuit of commerce and culture from Atlanta to Raleigh, with the all the migration that the transportation infrastructure brings. Gaston is part of the larger Charlotte-Concord-Rock Hill metropolitan statistical area with an estimated 2009 population of 1,745,524, a large increase of the 2000 census tally of 1,330,448. Up until the 2008 financial crash, the economic prosperity of the greater Charlotte region brought not only migrants from dying industrial areas in the Northeast and Midwest but also a vast number of immigrants from beyond the borders of the United States. Gastonia itself witnessed an 8.2% population growth rate between 2000 and 2010, and large numbers of new Latino, Asian, African and other migrants contributed to these totals.

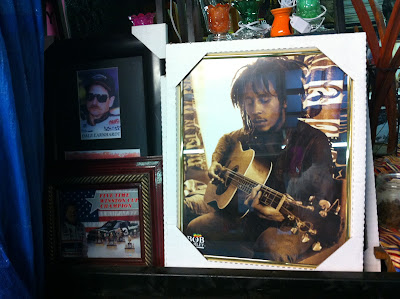

The Dallas flea market offers a fine indicator of the economic and demographic changes that have reshaped Gaston County over the last twenty years. Home to trucking and bartering in all things cheap, defective, reused, copied, stolen, unregulated and possibly illegal, it offers a place for enterprising people to make something out of next to nothing, from bootleg CDs and bizarre household nicknacks to low-priced necessities for families struggling to stretch every dollar. Its complexion has surely changed in the years since it was a dusty outpost of good old boys chatting and haggling in the Southeastern Sunday morning heat, and the material culture of the flea market -- Mexican wrestling masks and pinatas side by side with Confederate flags, 50 Cent remixes and Earnhardt encomia -- reveals how commerce can bring people of different origins and ideologies into the same space. Indeed, it is one of the few spaces in Gaston County where people of different races, religions, and immigration status regularly come into contact with each other.

A Saturday Morning at the Flea Market

A Saturday Morning at the Flea Market

KY gel and a gonorrhea test -- everything you need to plan for a big weekend.

Many of our photos were taken from oblique angles. People often do not like having their picture taken, of course, but the flea market brings with it many other issues of intrusion and anxiety where documentation is concerned. Anyone with a camera who comes into another person's world may be an unwelcome intruder, and although I went to high school around the corner and have been coming to the flea market for years, I am still an outsider -- especially when I'm holding up my phone to take pictures. Some shoppers and sellers at the market might have their own suspicions about who was taking pictures: undocumented immigrants, for example, might wonder if the INS or the local police were monitoring them, especially given the recent passage of bills in states such as Arizona and Georgia that gave local authorities the right to profile and harass immigrants. At least one food seller instructed his employees not to let me take pictures of the food they were selling. When I was asked why, the young woman said, "I just work here," although I imagine they might have been concerned about a visit from the Gaston County Health Department. We also did not take many direct photos of the "Out of My Cold Dead Hands"-style gun dealers because they might think we were agents of Obama's oppressive regime and they are, of course, armed.

.

1990s R&B and 1970s punk are neighbors at the Inner Hippie Shop, one of the vendors that operates within several closed hangar/warehouse buildings at the market. Other memorabilia includes framed photographs of classic jazz musicians, Bob Marley, and Dale Earnhardt -- an amalgam that strays over the boundaries of standard head-shop/counterculture fare.

Ismaili, a Turkish emigre, sells iPhone accessories. Note his scowling colleague with the eye patch in the back.

We generally tried not to take pictures of people's faces when they could be targeted for any kind of prosecution for what they were selling (e.g. see photos of bootleg CDs and DVDs without the merchants). It is no guarantee that a local cop or an RIAA/MPAA crusader will not randomly click on this blog and decide to "crack down" on these small sellers; indeed, in the IRB era, our project of documenting the flea market raises a lot of thorny issues. Are we obligated not to take photos of this social arena for fear that somehow, someone there might be threatened as a result? Is there any scholarly or journalistic imperative to create a record of this place and the people there? Should we have to get permission from everyone whose photo we would take, and if so, what are the implications for photojournalism? Should people only be depicted in the way they want to be depicted -- and not depicted at all if they say no?

Sandra's Simply Sinful Side Items, home of the fried Oreo, fried cheese danish and, of course, funnel cakes.

At the end of the morning we sample the legendary fried Oreos, drizzled with chocolate syrup and caramel.

.

The Flea Market as Historical Crossroads

It goes without saying that people have long associated trade and marketplaces as transnational spaces of interaction. In the pre modern and early modern world, Timbuktoo, Baghdad, London, and what was then Constantinople and today Istanbul, provide only a few spaces of this economic cosmopolitanism. Adam Smith saw civilization in free markets and capitalism’s invisible hand. The Islamic religious prophet Muhammad was a trader. Any high school history teacher worth his or her salt will tell you that trade is one of the main forms of cultural diffusion, enhancing the spread of language, religions, ideas, and products. These seem to be obvious facts.

So perhaps it should come as no surprise when Professor Cummings points to the Dallas, NC flea market as an amalgamation of transnational kitch. The professor’s points about immigration are well taken. A 2004 Economist article pointed out the increasingly suburbanized nature of immigration. For example, as of 2000, more immigrants resided in suburbs than cities and the numbers continued to rise. Furthermore, this suburbanized migration proved as true in New York and Chicago as it did in newer sites like Las Vegas, Washington D.C., and yes, Raleigh Durham. It happens fastest in the new “emerging gateways” of Dallas, TX and Professor Cummings’s southern jewel, Atlanta (Economist, “Immigration into the Suburbs”, March 11, 2004).

Cities like Chicago have long exhibited this sort of travel vista via marketplaces. For example, Maxwell Street market in Chicago began on Chicago’s west side over 120 years ago. The flea market, located on predictably, Maxwell Street, stretched from 16th Street all the way to Halsted Avenue. Forced to move in 1994 by a larger more moneyed transnational institution, the University of Illinois Chicago, the market landed on Canal Street in 1994 staying there until 2008 when it was forced by area businesses to relocate to the River North area along Desplaines Street between Roosevelt Road and Harrison Street. As one vendor admitted, “Flea markets such as Maxwell Street don't fit the changing image of the area.” Though it has long been heralded as multicultural space, who predominated usually developed accordance with migration to the city. What began with Russian Jews gave way to Poles who then receeded as African American migrants from the South became a dominant presence to today, where Mexican immigrants define the market. In fact as a Chicago chef Rick Bayless pointed out on a recent episode of the Travel Channel’s Bizarre Foods, Chicago has become the artisanal tortilla capital of the world. Moreover, some traditional Mexican cooking is more available in the city of Big Shoulders due to the wider availability of ingredients, which partially reflects the Midwestern agricultural hinterland that supports the metropolitan area. As with any change, some viewed the market’s current configuration with a sense of loss, "I miss the hot dog stands and the smell of onions," noted on longtime customer. "And pork chop sandwiches. Some of that comes with the changes in ethnicity. Today, you have a lot of taco stands."

Still, one should always remember the multi directional nature of these kind of spaces even when located in “semi-rural” or suburban locals. Mike Davis explores these locations in his work on Latino immigrants in America. In Magical Urbanism, Davis notes the more traditional insights in this regard such as whole “transnational communities” residing in one city block in L.A. but also draws attention to the place transnational suburbs have come to occupy for Latino immigrants. Remittances from work fuel rural development in Mexico, while creating a transnational flow of capital and people to these burgeoning suburban/metropolitan communities. “More than ever, repatriated “migradollars” (an estimated $8 billion to $10 billion annually during the 1990s) are a principal resource for rural communities throughout Mexico and Central America. Surpassing sugar and coffee, they are now the largest source of foreign exchanged in the Dominican and Salvadorean economies.” (Davis, 80) Global restructuring forces traditional communities to juggle capital and people between “two different, place rooted existences.” (80) Davis describes these connections between places like Dallas, NC and Puebla, Mexico as “economic and cultural umbilical cords.” (80) In this way, the “sending communities” serve as “transnational suburbs” distant from places like Atlanta, New York, or Miami, but as “fully integrated inot the economy of the immigrant metropolis as their own nation-state.” (80)

The power of these places is not confined to economics. Mexican politicians have been known to purchase media advertisements in American urban areas enticing Mexican nationals to vote from their homes in metropolitan areas of San Diego, Chicago, New York, and elsewhere. When the Dominican Republic’s dictatorial president Joaquin Balaguer exiled leading Dominican dissidents to New York, the Big Apple became the “main base for the country’s oppositional politics.” When political reforms relaxed the once authoritarian government’s grip on the nation, New York remained “the second home for the republic’s turbulent political life.” Davis notes it probably should then be no surprise that when Leonel Fernandez Reyna, who grew up on New York’s upper west side, won the nation’s 2004 presidency. Reyna still held a green card and fully expected to split his time between Manhattan and the D.R making Reyna perhaps the first transnational migrant ever elected to such an office. (84)

Still, if one believes the Economist, the Sunbelt is the future of immigration. After all, sprawl, a defining trait of many Sunbelt metropolitan areas, attracts immigrants. “Now, as sprawl consumes an ever-widening swathe of cornfields and meadows, immigrants are close behind," the Economist declares. "Who else will cut the grass, clean the houses or flip the burgers of suburbanites?” However, as has been seen in Queens, NY and elsewhere, immigrants can also generate what Saskia Sassen has called “low level gentrification.” Immigrant purchases and home starts in the greatest borough of New York spurred development. This points to the bifurcated nature of today’s immigration where on the one hand you have English speaking college educated legal immigrants and non-English speaking, poorly educated, and largely unskilled undocumented migrants: “Indian doctors and engineers represent the first group, Mexican day-labourers the second.” Granted, it is unlikely the Dallas flea market serves as a site for the H-1 Visa set, but as Leonel Fernandez Reyna illustrates, that vendor you bought the velvet Bob Marley picture from just might the next President of somewhere.

.

The Flea Market as Historical Crossroads

It goes without saying that people have long associated trade and marketplaces as transnational spaces of interaction. In the pre modern and early modern world, Timbuktoo, Baghdad, London, and what was then Constantinople and today Istanbul, provide only a few spaces of this economic cosmopolitanism. Adam Smith saw civilization in free markets and capitalism’s invisible hand. The Islamic religious prophet Muhammad was a trader. Any high school history teacher worth his or her salt will tell you that trade is one of the main forms of cultural diffusion, enhancing the spread of language, religions, ideas, and products. These seem to be obvious facts.

So perhaps it should come as no surprise when Professor Cummings points to the Dallas, NC flea market as an amalgamation of transnational kitch. The professor’s points about immigration are well taken. A 2004 Economist article pointed out the increasingly suburbanized nature of immigration. For example, as of 2000, more immigrants resided in suburbs than cities and the numbers continued to rise. Furthermore, this suburbanized migration proved as true in New York and Chicago as it did in newer sites like Las Vegas, Washington D.C., and yes, Raleigh Durham. It happens fastest in the new “emerging gateways” of Dallas, TX and Professor Cummings’s southern jewel, Atlanta (Economist, “Immigration into the Suburbs”, March 11, 2004).

Cities like Chicago have long exhibited this sort of travel vista via marketplaces. For example, Maxwell Street market in Chicago began on Chicago’s west side over 120 years ago. The flea market, located on predictably, Maxwell Street, stretched from 16th Street all the way to Halsted Avenue. Forced to move in 1994 by a larger more moneyed transnational institution, the University of Illinois Chicago, the market landed on Canal Street in 1994 staying there until 2008 when it was forced by area businesses to relocate to the River North area along Desplaines Street between Roosevelt Road and Harrison Street. As one vendor admitted, “Flea markets such as Maxwell Street don't fit the changing image of the area.” Though it has long been heralded as multicultural space, who predominated usually developed accordance with migration to the city. What began with Russian Jews gave way to Poles who then receeded as African American migrants from the South became a dominant presence to today, where Mexican immigrants define the market. In fact as a Chicago chef Rick Bayless pointed out on a recent episode of the Travel Channel’s Bizarre Foods, Chicago has become the artisanal tortilla capital of the world. Moreover, some traditional Mexican cooking is more available in the city of Big Shoulders due to the wider availability of ingredients, which partially reflects the Midwestern agricultural hinterland that supports the metropolitan area. As with any change, some viewed the market’s current configuration with a sense of loss, "I miss the hot dog stands and the smell of onions," noted on longtime customer. "And pork chop sandwiches. Some of that comes with the changes in ethnicity. Today, you have a lot of taco stands."

Still, one should always remember the multi directional nature of these kind of spaces even when located in “semi-rural” or suburban locals. Mike Davis explores these locations in his work on Latino immigrants in America. In Magical Urbanism, Davis notes the more traditional insights in this regard such as whole “transnational communities” residing in one city block in L.A. but also draws attention to the place transnational suburbs have come to occupy for Latino immigrants. Remittances from work fuel rural development in Mexico, while creating a transnational flow of capital and people to these burgeoning suburban/metropolitan communities. “More than ever, repatriated “migradollars” (an estimated $8 billion to $10 billion annually during the 1990s) are a principal resource for rural communities throughout Mexico and Central America. Surpassing sugar and coffee, they are now the largest source of foreign exchanged in the Dominican and Salvadorean economies.” (Davis, 80) Global restructuring forces traditional communities to juggle capital and people between “two different, place rooted existences.” (80) Davis describes these connections between places like Dallas, NC and Puebla, Mexico as “economic and cultural umbilical cords.” (80) In this way, the “sending communities” serve as “transnational suburbs” distant from places like Atlanta, New York, or Miami, but as “fully integrated inot the economy of the immigrant metropolis as their own nation-state.” (80)

The power of these places is not confined to economics. Mexican politicians have been known to purchase media advertisements in American urban areas enticing Mexican nationals to vote from their homes in metropolitan areas of San Diego, Chicago, New York, and elsewhere. When the Dominican Republic’s dictatorial president Joaquin Balaguer exiled leading Dominican dissidents to New York, the Big Apple became the “main base for the country’s oppositional politics.” When political reforms relaxed the once authoritarian government’s grip on the nation, New York remained “the second home for the republic’s turbulent political life.” Davis notes it probably should then be no surprise that when Leonel Fernandez Reyna, who grew up on New York’s upper west side, won the nation’s 2004 presidency. Reyna still held a green card and fully expected to split his time between Manhattan and the D.R making Reyna perhaps the first transnational migrant ever elected to such an office. (84)

Still, if one believes the Economist, the Sunbelt is the future of immigration. After all, sprawl, a defining trait of many Sunbelt metropolitan areas, attracts immigrants. “Now, as sprawl consumes an ever-widening swathe of cornfields and meadows, immigrants are close behind," the Economist declares. "Who else will cut the grass, clean the houses or flip the burgers of suburbanites?” However, as has been seen in Queens, NY and elsewhere, immigrants can also generate what Saskia Sassen has called “low level gentrification.” Immigrant purchases and home starts in the greatest borough of New York spurred development. This points to the bifurcated nature of today’s immigration where on the one hand you have English speaking college educated legal immigrants and non-English speaking, poorly educated, and largely unskilled undocumented migrants: “Indian doctors and engineers represent the first group, Mexican day-labourers the second.” Granted, it is unlikely the Dallas flea market serves as a site for the H-1 Visa set, but as Leonel Fernandez Reyna illustrates, that vendor you bought the velvet Bob Marley picture from just might the next President of somewhere.