In John Sayles’s 1996 classic Lone Star, the filmmaker/essayist included a scene between two older romantically involved military officers, one a white man and the other a black woman. In a discussion about meeting her family, the male officer asked if his race would be an issue, and his romantic counterpart commented that her family figured she was a lesbian at this point, so any man proved an improvement. To which he replied, roughly, “It’s always good to see one prejudice defeated by another one.” Welcome to the modern American mind: a complex crisscrossing of biases and open-mindedness, a cauldron overflowing with solidarities and conflicts.

Enter Jonathan Demme’s 2008 film Rachel Getting Married. Filmed in the handheld, philosophical style of the waning Dogme 95 movement, the movie juxtaposes the dissolution of the American middle class family with a new, possibly utopian multicultural community. A.O. Scott cited the influence of avant-garde film; the movie owed a “clear debt to the ostentatiously austere methods of [Dogme 95],” wrote Scott, “The audience only hears music that the people in the movie hear as well, and the proceedings are recorded by a busily wandering video camera.” Of course, the New York Times critic also noted Demme’s softer edges as Rachel Getting Married lacked the “sadistic” edges of the famed Dogme director Thomas Vinterberg. The home film experience of the Dogme approach adds a gauzy earthiness to a story about collapse and reconstruction. This stylistic approach contributes to a broader message of unselfconscious diversity, one where a home film offers only cinema vérité, rather than commentary. Demme himself claimed to be attempting to create the “most beautiful home movie ever."

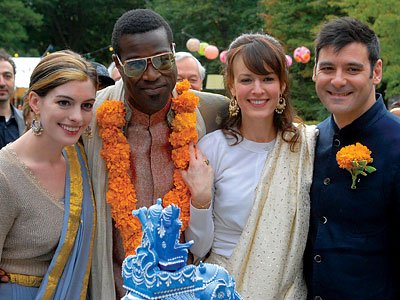

While Rachel Getting Married focuses on the awkward reintegration of Rachel’s sister Kym (Anne Hathaway), who receives temporary leave from her drug rehabilitation program during the older sister’s wedding, a central aspect of the work is the idea of loss and recovery – physically, emotionally, and existentially. One might argue, as some academics have, that the multicultural milieu of the film serves to portray America as a burgeoning mix of religions, races, and ethnicities comfortable enough to inhabit the same wedding for several days, with the only conflict unfolding among the white family members of Rachel’s brood.

Over the course of the weekend, the audience is introduced into a sprawling social landscape. TV on the Radio singer Tunde Adebimpe plays Rachel’s black fiancée, Sidney, while numerous yellow and brown faces abound. The wedding itself is a mishmash of cultural reference points, thrown together in Cuisinart fashion: a Brazilian samba dance troupe appears during the reception and the BBQ-style dinner featured waiter service by the groom and bride, both of whom are dressed in Asian/Buddhist style garb. Again, like a handheld video observing these events, no direct mention of this diversity emerges; as Scott acknowledges, “these facts are never mentioned by anyone in the movie, which gathers races, traditions and generations in a pleasing display of genteel multiculturalism. It’s a big, messy gathering even without Kym’s melodrama, so there may be no time for expressions of prejudice or social unease.”

However, not all critics viewed Demme’s vision so benignly. Time’s Richard Schickel described the family as “smugly PC,” gathering to celebrate their “perfectly balanced daughter” Rachel. Moreover, Schickel took issue with Demme’s broader aims: “This is not just a wedding, however; it is also a sociopolitical statement, for the groom is a handsome black man, scion of a family that is far more conventional and bourgeois than the bride's family, and especially the bride's sister, Kym.”

Multiculturalism has long served as PC whipping boy: the ivory tower fascists imposing a relativistic norm on an unwitting populace. However, not all academics have supported the multicultural ideal. For example, Lisa Lowe views the emergence of multiculturalism as the ultimate dodge, focusing only on the future and present, ignoring the past inequalities and grievances that have shaped current conditions. “The nation proposes American culture as a the key site for the resolution of inequalities and stratifications that cannot be resolved on the political terrain of representative democracy,” Lowe writes, “then that culture performs that reconciliation by naturalizing a universality that exempts the ‘non-American’ from its history of development or admits the ‘non-American’ only through a ‘multiculturalism’ that aestheticizes ethnic differences as if they could be separated from history.” (9)

Rachel’s family certainly knows a thing or two about aestheticizing difference. This bunch of upper-middle class white northeasterners go to great lengths to demonstrate their broad-mindedness and cultural sophistication at the wedding, by stocking it with borrowed gestures from other people’s cultures. Diversity is converted into a consumer good – something to be shopped for, and, at most, put on and taken off like an article of clothing. With their Brazilian dances and pseudo-Buddhist costumes, one wonders if dashikis and a Bollywood dance number could not be far behind. Do these liberal white people have no traditions of their own?

The showy “diversity” of the weekend’s events actually underlines the racial divide within the wedding. As critics have noted, the film had little time to explore any tension between the two families because the bride's side was in a state of perpetual meltdown – but the black characters were also total ciphers. Sidney and his family were like wallpaper. They appear to be kind, patient people, but they have virtually no role in the film except to serve as the backdrop for the white family’s explosive psychodrama. Rachel, Kym and their brood barely seem to notice that the other characters are there, so consumed are they in their own narcissistic score-keeping and resentment.

Ironically, the family's upper class, liberal, forward-thinking ways could not make up for their own profoundly damaged psyches. Rachel and Kym’s mother has been a reclusive alcoholic ever since the tragedy that shattered their family years earlier. She appeared to be uncomfortable attending the wedding; perhaps she resented the others for their happiness, or perhaps she felt like they didn't really want her there, since she blames herself (and they blame her) for an accident that claimed the life of a young family member long ago.

What happened to the white boomers, as represented by Rachel’s parents? They drank and did drugs, got into world music, searched for self actualization, and neglected their children. They also got down with the brown, as the music and fashion at their daughter’s wedding indicate. But all that hippie-dippy love and compassion and open-mindedness didn't extend to trying to understand and forgive their daughter Kym for her destructive behavior.

In this light, does the America that Demme constructs in Rachel Getting Married represent a more progressive, diverse society, or does it simply paper over historical fissures and grievances that continue to affect our conceptions of race, culture, family, tradition, and so forth? This is not to say that social groups should hold tightly to anger or historical resentments; rather, we all need to be attentive to such histories as we struggle for greater social, political, and economic integration. As the old and, yes, triumphantly lame G.I. Joe PSA’s used to announce, “Knowing is half the battle.” One might frame this more intellectually, pointing to Emile Durkheim’s observation: if one wants to escape psychological and social prisons, one must know he or she is in one.

This brings us to a point of friction between the two authors of this piece. What was the filmmaker’s intent? Did Demme want the audience to envision a utopian multicultural future, or is his wandering, Dogme-like gaze meant to reveal the foibles and hypocrisy of liberal upper middle class America’s fetish for the “other”? Does Rachel’s family participate in what amounts to little more than modern American Orientalism, akin to Said’s nineteenth century version?

Getting at Demme’s intentions remains fraught with difficulty. The director purposely made the father of the bride a record producer in order to provide an explanation for the participant’s stumbling diversity and a soundtrack without a soundtrack. As Demme said in a 2008 interview:

I thought, ‘If we make their father a music industry executive, then maybe, if I was him, I would have Sister Carol East come over from Brooklyn and perform live.’ He would have to do something like that. And Robyn Hitchcock, he would fly Robyn Hitchcock in. So I knew that we could use as much of that stuff as suited the movie. I also thought that a great way to deliver the joy and euphoria that should and hopefully would come from a beautiful ceremony would be through dance, and dancing to live music and responding to live music is that much more exciting than a deejay spinning and stuff. And I’m forgetting the fact that Jenny [Lumet] had written in that, for no apparent reason, suddenly there’d be a Brazilian samba band there. So this was just pushing that envelope as far as seemed reasonable.So does sheer musical exuberance explain Demme’s intent, or is it something else? Demme seems to believe in Rachel’s wedding as a tableaux of a harmonious, beautiful mélange of colors and cultures – the same aim that Rachel and Sidney may have hoped for when planning the ceremony. That being said, it remains hard not to see the film’s main characters as much more than self-involved consumers who, much like Demme himself, use culture as a fashionable backdrop for their own interpersonal struggles.

RR and AC

Another great article. I like that you are very honest and direct to the point.

ReplyDeleteTerm Papers

Thank you. I'd seen this movie a while back and just watched it again. Something about it grated on my nerves, and you hit the nail on the head.

ReplyDelete