What would Kobe say?

Jeremy Lin is a good player but all the hype is because he's Asian. Black players do what he does every night and don't get the same praise.

It is precisely the unfixed liminality of the Asian immigrant – geographically, linguistically, and racially at odds with the context of the “national” – that has given rise to the necessity of endlessly fixing and repeating such stereotypes.

-- Lisa Lowe, Immigrant Acts, 19

Floyd Mayweather is not a brain surgeon. The man punches for a living and he punches very well. However, all that head trauma must have knocked more than few synapses loose, why would Mayweather begrudge the new Asian American icon Jeremy Lin of his place in American sports lore? Mayweather has a long history of this from his choice to wear a sombrero when fighting Oscar De La Hoya to his numerous comments regarding Manny Pacquiao (who Mayweather once confusingly mocked for eating “sushi” which of course is Japanese not Filipino). Certainly, he’s not the only African American to begrudge an Asian athlete success. Shaquille O’Neal famously dismissed Yao Ming with the comment, "Tell Yao Ming, 'ching-chong-yang-wah-ah-soh." So what’s this all about and what does it tell us about 21st century America?

To be fair, Mayweather has a point. While Yao Ming and a handful of other Chinese basketball stars have successfully navigated the league, the league has NEVER seen an Asian American basketball talent perform at this level on this stage. That Lin plays for New York no doubt helps - the Knicks remain one of the league’s franchise teams. Even when they suck, and the Knicks have sucked mightily in recent years, the team has always turned a profit. So yes, the combination of Lin’s ethnicity/race and his location, the Big Apple, and his team, the New York Knickerbockers serve to highlight his success in ways that a player in Minnesota simply can’t. With that said, seven straight wins for a team without one of its key players matters, no matter the race or ethnicity of the player dragging the Knicks to a possible playoff spot.

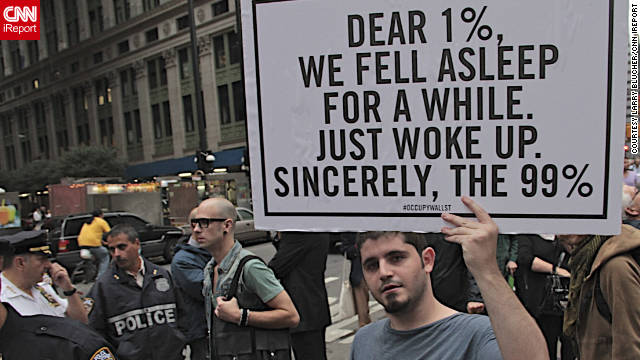

Yet, Mayweather also points to a reality of American race relations: as the nation’s diversity increases over the 21st century, we will need to figure out how to discuss and think about race in America. The black white binary that dominated American racial thought – popularly and academically - seems to have little relevance in a nation where Asian American and Latino American residents seem to increase their numbers every year. Racism affects each of these groups, but in different manners and through different pathways. No one doubts the long established prejudice against Black citizens in America. The historical legacy of slavery and Jim Crow remain central aspects of our nation’s history. Yet, Asian Americans and Latinos, notably Mexican nationals and Mexican Americans, have their own histories of struggle.

The transnational nature of Asian American and Latino identity adds confusion for many observers. It goes without saying that media outlets like ESPN have noted how the Chinese government remains wary of Lin as a figure: 1) for his Taiwanese background and 2) for his devout religiosity. While ESPN and other outlets note this relevant fact, writers like Lisa Lowe and Charlotte Brooks have noted the stereotype of the “perpetual foreigner” attached to Asian American citizens has often served to undermine their status. With the internet, twitter, and the countless forms of social media out there, undoubtedly, Chinese citizens will be drawn to the Jeremy Lin narrative and ESPN should discuss this. However, it also reinforces the idea that Asian Americans maybe citizens but they belong to different shores. Overall, the media’s behavior has been mostly positive, though there have been several hiccups along the way as USA today documented Thursday (2/16/2012).

In Alien Neighbors, Foreign Friends, Brooks charts the intense discrimination and segregation endured by West Coast Japanese and Chinese American populations in the first half of the 20th century. Even when finally accepted by white homeowners, this acceptance hinged on the international connections of Asian American populations rather than their place as American citizens. Brooks points out that this “transnational identity” undermined Chinese claims to national membership as they were seen as permanent foreigners, albeit welcome ones. Also, as with the Japanese American example, the arrival of larger numbers of African American residents recast white homeowner concerns that now Chinese Americans came to be seen, along with other Asian Americans, as the “model minority,” to be contrasted with more “troublesome” racial/ethnic groups. Accordingly, Brooks suggests that American interventionism in Asia along with pervasive domestic fears of communist infiltration and agitation “spurred white Californians to reconsider the impact of their segregationist decisions. In the end, the deepening Cold War short circuited the emerging pattern and replaced it with a far different one.” (193) Really, considering that the nation interned its Japanese American population during WWII, these shifts in attitudes are notable.

White homeowners continued to exhibit a desire to live apart from nonwhites; even when they accepted Chinese or Japanese American neighbors, they did so out of a sense of anti-communism rather than any nod toward racial equality. One white resident, who supported Nisei WWII veteran Sam Yoshira’s attempt to buy a home in Southwood (South San Francisco), commented, “My property values aren’t as important as my principles.” (Brooks, 206) Such admissions reveal not only latent racial attitudes but also the effect of FHA/HOLC housing policies that dismissed communities with nonwhites as eligible for home loans and the like.

Even before these developments, as writers like Nayan Shah and others have pointed out, Asians were denied the right to own land in many western states (look up the Alien Land Act in CA 1913) and later prevented from achieving naturalized citizenship (they were labeled unable to assimilate). US policymakers depicted America's violent occupation of the Philippines much like Rudyard Kipling's "White Man's Burden": bringing the torch of civilization and democracy to savages. To make matters worse, as Paul Kramer points out in The Blood of Government, despite living under US imperial rule for several decades of the 20th century where US imposed education systems stressed American ideals of equality, Filipinos encountered violent racism on the nation's western shores when they migrated in the early decades of the century. Filipinos of the 1930s and 1940s had been raised under “benevolent assimilation” which cast America in idealistic and unrealistic terms. The history of struggle against American forces no longer existed (erasure through education) such that Filipino immigrants to the US articulated a sanitized version of US-Philippines history, while remaining shocked at the overt racism that few American educators bothered to mention.

In Alien Neighbors, Foreign Friends, Brooks charts the intense discrimination and segregation endured by West Coast Japanese and Chinese American populations in the first half of the 20th century. Even when finally accepted by white homeowners, this acceptance hinged on the international connections of Asian American populations rather than their place as American citizens. Brooks points out that this “transnational identity” undermined Chinese claims to national membership as they were seen as permanent foreigners, albeit welcome ones. Also, as with the Japanese American example, the arrival of larger numbers of African American residents recast white homeowner concerns that now Chinese Americans came to be seen, along with other Asian Americans, as the “model minority,” to be contrasted with more “troublesome” racial/ethnic groups. Accordingly, Brooks suggests that American interventionism in Asia along with pervasive domestic fears of communist infiltration and agitation “spurred white Californians to reconsider the impact of their segregationist decisions. In the end, the deepening Cold War short circuited the emerging pattern and replaced it with a far different one.” (193) Really, considering that the nation interned its Japanese American population during WWII, these shifts in attitudes are notable.

White homeowners continued to exhibit a desire to live apart from nonwhites; even when they accepted Chinese or Japanese American neighbors, they did so out of a sense of anti-communism rather than any nod toward racial equality. One white resident, who supported Nisei WWII veteran Sam Yoshira’s attempt to buy a home in Southwood (South San Francisco), commented, “My property values aren’t as important as my principles.” (Brooks, 206) Such admissions reveal not only latent racial attitudes but also the effect of FHA/HOLC housing policies that dismissed communities with nonwhites as eligible for home loans and the like.

Even before these developments, as writers like Nayan Shah and others have pointed out, Asians were denied the right to own land in many western states (look up the Alien Land Act in CA 1913) and later prevented from achieving naturalized citizenship (they were labeled unable to assimilate). US policymakers depicted America's violent occupation of the Philippines much like Rudyard Kipling's "White Man's Burden": bringing the torch of civilization and democracy to savages. To make matters worse, as Paul Kramer points out in The Blood of Government, despite living under US imperial rule for several decades of the 20th century where US imposed education systems stressed American ideals of equality, Filipinos encountered violent racism on the nation's western shores when they migrated in the early decades of the century. Filipinos of the 1930s and 1940s had been raised under “benevolent assimilation” which cast America in idealistic and unrealistic terms. The history of struggle against American forces no longer existed (erasure through education) such that Filipino immigrants to the US articulated a sanitized version of US-Philippines history, while remaining shocked at the overt racism that few American educators bothered to mention.

|

| The Warriors didn't play him much but they pimped him for AHN |

Ironically, considering how Asian men and women are sexualized in modern America, white observers feared Filipinos, with their flashy clothes and sensual nature would seduce white women while Chinese men would ply innocent white ladies with gifts and opium. As for Asian women, one need only look at the Page Act of 1875 (it basically prevented Chinese women from migrating to the US using morality and their lack of male attachment as factors contributing to their rejection), to know that American officials viewed most Chinese women as sexually licentious and disease ridden. I won’t even get into the Chinese Exclusion Act (1882), the Gentlemen’s Agreement or the numerous “driving out” campaigns along the West Coast in which Chinese and Japanese populations were forcibly and violently driven from towns. Needless to say, these campaigns resulted in economic distress, emotional strain, and often numerous deaths. In this environment, like Blacks in the South, Asian populations provided elites with a scapegoat for the larger economic ramifications of expanding capitalism and corporate development that largely punished local working class white communities. Collectively, the Page and Chinese Exclusion Acts served as foundational texts for immigration laws (often restrictions based on race, class, gender, and ethnicity) of the 1920s to today (see Erika Lee).

|

| Rudyard Kipling would be proud |

When addressing Mayweather’s comments, it helps to consider these facts. Though Asian Americans endured stark racism in the first half of the 20th century, the arrival of large numbers of African Americans on the West Coast via the Great Migration (and the Second Great Migration) drove whites to accept Asian Americans as the lesser of two evils. While I doubt Mayweather had such historical constructs in mind, one can see parallels in today’s American culture that might drive some African Americans to resent Lin’s success. After all, as recently as the mid-1990s, Douglass Massey and Nancy Denton noted that though housing segregation persists, Black Americans continue to endure its most pernicious forms while Asian and Latino Americans have been able to suburbanize at higher levels including integration into white communities. Moreover, plenty of East Asian and South Asian Americans have expressed racism towards Black Americans as well. To paraphrase Toni Morrison, the first thing every immigrant has done once reaching America was illustrate how he or she wasn’t black. So some African Americans surely see themselves as more “American” than recent Asian or Latino American arrivals yet economically, they have yet to enjoy the same level of success. Granted Obama’s presidency and the rise of a significant Black American middle class blunts this somewhat, yet still for some people, these issues bring up negative feelings.

Lin himself acknowledges that even when playing for Harvard, it was not unusual to hear racial slights – comments regarding “sweet and sour pork” – or the slur, “chink”. Such obvious outbursts of racism don’t really deserve our attention, whatever place they come from, nearly everyone condemns them. No, it’s the subtle institutional form that plays a factor here. ESPN analyst and former NBA player Tim Legler suggested that Lin’s lack of opportunity may have also played a factor in his late bloom. Legler, who is white, noted that while Black players in the NBA believed he was a capable shooter, front office executives and some coaches, most of whom were white, viewed him as a liability largely because of his race. As Legler pointed out recently, Lin probably endured similar doubts. Granted, being from Harvard didn't help, most people don't recognize the Ivies for their basketball talent.

If Asians were denied citizenship, land ownership, and decent housing because of fears about disease, morals, and sexuality in the first half of the century, Lin’s ascent had been mitigated by nearly opposite racial concerns: Asian Americans' rise to “model minority” status meant they were great college students, lawyers, and IT specialists, not athletes. Of course, this model minority status probably rubbed some minorities the wrong way. Numerous writers have argued that the “model minority” construct, promoted by White American and sections of the Asian American community arose in the 1960s and 1970s as rebuke to other minority groups protesting for equal rights, notably the Chicano and Black Power movements. Grantland editor Jay Caspian Kang, who is Asian American himself and frequently writes about race for the site pointed out that though white Americans promoted this construct, segments of the Asian American community held some culpability:

Lin himself acknowledges that even when playing for Harvard, it was not unusual to hear racial slights – comments regarding “sweet and sour pork” – or the slur, “chink”. Such obvious outbursts of racism don’t really deserve our attention, whatever place they come from, nearly everyone condemns them. No, it’s the subtle institutional form that plays a factor here. ESPN analyst and former NBA player Tim Legler suggested that Lin’s lack of opportunity may have also played a factor in his late bloom. Legler, who is white, noted that while Black players in the NBA believed he was a capable shooter, front office executives and some coaches, most of whom were white, viewed him as a liability largely because of his race. As Legler pointed out recently, Lin probably endured similar doubts. Granted, being from Harvard didn't help, most people don't recognize the Ivies for their basketball talent.

If Asians were denied citizenship, land ownership, and decent housing because of fears about disease, morals, and sexuality in the first half of the century, Lin’s ascent had been mitigated by nearly opposite racial concerns: Asian Americans' rise to “model minority” status meant they were great college students, lawyers, and IT specialists, not athletes. Of course, this model minority status probably rubbed some minorities the wrong way. Numerous writers have argued that the “model minority” construct, promoted by White American and sections of the Asian American community arose in the 1960s and 1970s as rebuke to other minority groups protesting for equal rights, notably the Chicano and Black Power movements. Grantland editor Jay Caspian Kang, who is Asian American himself and frequently writes about race for the site pointed out that though white Americans promoted this construct, segments of the Asian American community held some culpability:

It has become standard issue for successful Asian Americans to just sort of avoid talking about race. This, I guess, makes sense along the spectrum of assimilation, but it's an inherently elitist stance that plays a bit too coy, especially in a country that has largely decided to turn a blind eye toward racism against Asian Americans. I have no doubt, given his comments in the past, that Lin thinks about his peculiar role in America's blackest network TV show. But for now, he and the Knicks have not said much about anything, really.

The larger point here is that Lin remains a symbol of 21st century America, positively and negatively. He embodies the kind of social and political changes that we need to acknowledge. Discussions of race in America must incorporate these complex dynamics to fully understand, how we got here. White America does not own a monopoly on racism or racial antipathy. It exerts its own prejudices and biases, but so do other communities.

Floyd Mayweather may be an ass, but his comments at least open up space for discussion. Hopefully, we can fill these spaces with a useful dialogue that helps us understand each other and our nation more completely. To be honest, the aforementioned King may have articulated the awkward role that race continues to play in this story best. Speaking to fellow Grantland editor Bill Simmons, Kang summed up the past two weeks neatly:

There's always going to be some shit kicked up by haters, but the outpouring of excitement and love has overwhelmed the usual racist clatter. That doesn't mean I haven't rolled my eyes a couple times or even gotten angry. But there's a difference between someone who says something a bit insensitive out of genuine enthusiasm and someone who is just trying to get off his bitter rocks. It's important to not hawk over Linsanity with that much vigilance; it's basketball and it's a bunch of dudes typing reactions on Twitter. There's just no reason to let a few racist assholes ruin the best party of the year. Yes, some of these comments have highlighted that we, as a society, don't treat all racism equally, but if you didn't know that already, you've been living in a hole somewhere. More important, if you can't look at Jeremy Lin and see why America is the greatest country in the world, well, then you don't understand America.

Who knows what the “greatest country in the world” is, but “Linsanity” makes me feel better about this one.

[Editors Note - To its credit, Grantland addressed the racial aspects of Lin's rise early and often. In addition to those articles mentioned above, Rembert Browne's recent essay only adds to the mix]

Ryan Reft