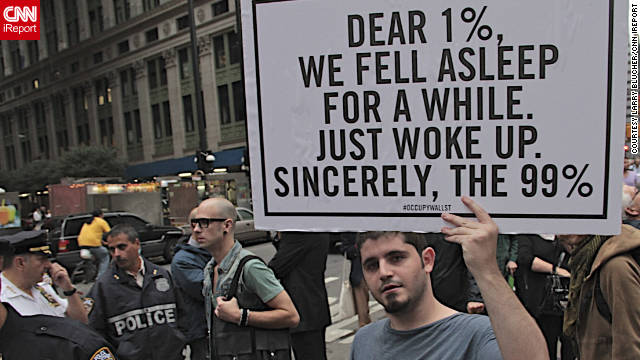

During a graduate seminar this Fall, we discussed Jefferson Cowie and Nick Salvatore’s excellent article on the New Deal, “The Long Exception,” and our thoughts inevitably turned to comparisons of the 1930s and the present moment. These were the early days of the Occupy movement, when the protests were first beginning to confuse those who believe every political action needs to come with a bullet-point policy platform, and critics of the Left were already sharpening their critique of the smelly, lazy folks who had nothing better to do than sit around in the park all day. To me, the protest seemed to function so beautifully because of its aimlessness. The inertia of its participants symbolized the problems of poverty, unemployment, and homelessness more perfectly than any statistic about jobless claims or any proposal for tackling the economic crisis ever could. I looked at it and saw Hooverville.

Yes, the Occupiers included many militant anarchists, some of whom espouse the creed of “Fuck work,” and the encampments inevitably included many people who were already permanently out of the labor force—homeless men and women who slept in the parks and public spaces before the Occupy movement arrived. But most of the participants represented a younger generation who looked to the future with little hope for success, as traditionally measured—the endless hours they spent idling in public space were a visible testament to the fact the bigger economy did not have a lot of use for them. If it did, they would be somewhere else—teaching school, building roads, packaging bad mortgages as valuable investments, or whatever it was that people did before our society starting hemorrhaging work.

Yes, the Occupiers included many militant anarchists, some of whom espouse the creed of “Fuck work,” and the encampments inevitably included many people who were already permanently out of the labor force—homeless men and women who slept in the parks and public spaces before the Occupy movement arrived. But most of the participants represented a younger generation who looked to the future with little hope for success, as traditionally measured—the endless hours they spent idling in public space were a visible testament to the fact the bigger economy did not have a lot of use for them. If it did, they would be somewhere else—teaching school, building roads, packaging bad mortgages as valuable investments, or whatever it was that people did before our society starting hemorrhaging work.

So Occupy has provided a powerful visual message of a system gone awry, in a way that thousands of individual foreclosures or firings never could. Such tragedies appear to be isolated incidents; they happen behind closed doors, in offices and factories; at their most noticeable, we see their traces in neighborhoods where dirty, mildewed toys and furniture pile up on the curbside, the remnants of a some unlucky local’s former home life.

I mention all this only because our class discussion of the contemporary crisis turned on such signs. The graduate students in the course said that they know, in an abstract sense, that there is a profound crisis affecting the country, but they admitted that the evidence of the ongoing, grinding recession was hard to find in the course of everyday life. They have homes; most of them have jobs and families; they are going to school; and when they go to Target, they do not see chaos in the streets or lines of people snaking around the corner next to a soup kitchen.

.

Actually, one can easily see such scenes in Atlanta on any day of the week and in any year in recent memory. The churches of downtown are nearly always surrounded by disheveled, dislocated individuals who wait for money, food, and help in general, but most Atlantans have been so long inured to seeing these people that it eventually stops making much of an impression. My first impression of Atlanta, when I visited over a decade ago, was that of “a giant Starbucks full of homeless people”—and in that regard it has not changed much, boom or recession or anything in between.

Nevertheless, my students and I can know that unemployment is high, home prices are at catastrophic lows, mortgages are under water and families are suffering from hunger and homelessness, yet American society somehow seems to be going happily about its business. The immortal image of the Depression is a bread line—a long queue of people in black and white, in trench coats and floral print dresses and fedoras, standing on a corner, waiting to eat. Or men selling apples on the street—presumably men who were lawyers or architects before the collapse. We think of ruined businessmen jumping from hotel room windows.

For better or worse, I do not know of too many Wall Street tycoons who felt compelled to end it all after destroying the livelihoods and savings of thousands, even millions of ordinary people around the world. If anything, they have taken their bonuses instead.

Of course, all these symbols might be described as a kind of Depression kitsch. For many people, the real Depression was probably not as deeply felt as we imagine, just as the 1960s for most Americans did not really mean smoking dope and jumping into leftist radicalism. (Look at any yearbook from 1967—you will probably see more crew cuts than love beads.)

But these images are what we think of when we think of the Depression, and the Great Recession of 2007-now does not seem to fit the bill. Perhaps the explanation is simply a Trumanism. The thirty-third president famously remarked that a recession is when your neighbor loses his job; a depression is when you lose yours. For a lot of people, maybe the current crisis does not hit close to home, especially if one comes from a prosperous, educated, solidly middle or upper class family. I know that many members of my family have been hit by layoffs and the threat of foreclosure or homelessness, but that may not apply to all of my students. I was surprised to see that almost no one in the class raised their hands when I asked if they knew someone who had gotten a college degree but could not find a job, or a good job. (I had assumed that was quite normal, although I am told that the unemployment rate for holders of a bachelor’s degree in Atlanta is actually 4%.)

I do not think it is just that the students at Georgia State University are privileged and insulated from economic hardship—far from it, in fact. The real reasons why the toll of today’s crisis seems invisible for many have to do with culture, policy, and the New Deal itself. Jefferson Cowie and Nick Salvatore’s perceptive argument in “The Long Exception” is that we should not look at the New Deal as the historical norm, from which we have deviated as the liberal welfare state has been dismantled since 1970s. Too many narratives, they suggest, assume that an interventionist economic policy that aims to ensure the public good by propping up employment and providing social services is the main current of American history, and the counterrevolution of Ronald Reagan and George Bush has somehow taken us off the track of normal historical development. Cowie and Salvatore suggest that the New Deal itself was the aberration, a set of policies that were out of step with the broad sweep of American politics. The 1980s and 1990s were not just a Second Gilded Age; they were America reverting to its norm, which before and after the New Deal era was always committed to individualism, property rights, and the free market.

Cowie and Salvatore make some excellent points. The 1880s and 1980s look a lot alike in some ways, and not just in terms of venal politcians and a general economic free-for-all. As Paul Starr has noted, the supposedly libertarian era of the late nineteenth century also saw morality campaigns against pornography and other forms of vice that mirrored the Reagan Era’s strange combination of free market ideology and puritanical hysteria about threats to public virtue.

But I am not sure that calling the New Deal an exception is quite right. It did represent a historical break, as Americans had to discard trusty bromides about limited government and individual initiative to consider the benefits of collective security. (Jennifer Klein has discussed the meaning of “security” as a new ideal for Americans in her excellent work on Social Security, insurance and healthcare.) The Depression was a crisis that forced a profound rethinking of American assumptions about government and policy, and I do not believe that we have truly abandoned this set of ideas, no matter how much we find rugged individualism seductive and the “nanny state” unacceptably un-American.

We still have Social Security. We still have food stamps and FHA loans and the minimum wage (at least technically—many people work for a lot less). We still have the Great Society addenda to the New Deal, and Medicare is one of the most politically explosive and technically problematic components of government today. No matter how much the Republican Party would like to end and/or privatize the program, they also realize its great utility as a sacred cow. All of these programs have at least ameliorated the most brutal effects of the economic meltdown, making life minimally bearable or sustainable for many people who would otherwise be hungry, jobless, homeless, sick, on the street—and potentially disruptive.

But these images are what we think of when we think of the Depression, and the Great Recession of 2007-now does not seem to fit the bill. Perhaps the explanation is simply a Trumanism. The thirty-third president famously remarked that a recession is when your neighbor loses his job; a depression is when you lose yours. For a lot of people, maybe the current crisis does not hit close to home, especially if one comes from a prosperous, educated, solidly middle or upper class family. I know that many members of my family have been hit by layoffs and the threat of foreclosure or homelessness, but that may not apply to all of my students. I was surprised to see that almost no one in the class raised their hands when I asked if they knew someone who had gotten a college degree but could not find a job, or a good job. (I had assumed that was quite normal, although I am told that the unemployment rate for holders of a bachelor’s degree in Atlanta is actually 4%.)

I do not think it is just that the students at Georgia State University are privileged and insulated from economic hardship—far from it, in fact. The real reasons why the toll of today’s crisis seems invisible for many have to do with culture, policy, and the New Deal itself. Jefferson Cowie and Nick Salvatore’s perceptive argument in “The Long Exception” is that we should not look at the New Deal as the historical norm, from which we have deviated as the liberal welfare state has been dismantled since 1970s. Too many narratives, they suggest, assume that an interventionist economic policy that aims to ensure the public good by propping up employment and providing social services is the main current of American history, and the counterrevolution of Ronald Reagan and George Bush has somehow taken us off the track of normal historical development. Cowie and Salvatore suggest that the New Deal itself was the aberration, a set of policies that were out of step with the broad sweep of American politics. The 1980s and 1990s were not just a Second Gilded Age; they were America reverting to its norm, which before and after the New Deal era was always committed to individualism, property rights, and the free market.

Cowie and Salvatore make some excellent points. The 1880s and 1980s look a lot alike in some ways, and not just in terms of venal politcians and a general economic free-for-all. As Paul Starr has noted, the supposedly libertarian era of the late nineteenth century also saw morality campaigns against pornography and other forms of vice that mirrored the Reagan Era’s strange combination of free market ideology and puritanical hysteria about threats to public virtue.

But I am not sure that calling the New Deal an exception is quite right. It did represent a historical break, as Americans had to discard trusty bromides about limited government and individual initiative to consider the benefits of collective security. (Jennifer Klein has discussed the meaning of “security” as a new ideal for Americans in her excellent work on Social Security, insurance and healthcare.) The Depression was a crisis that forced a profound rethinking of American assumptions about government and policy, and I do not believe that we have truly abandoned this set of ideas, no matter how much we find rugged individualism seductive and the “nanny state” unacceptably un-American.

We still have Social Security. We still have food stamps and FHA loans and the minimum wage (at least technically—many people work for a lot less). We still have the Great Society addenda to the New Deal, and Medicare is one of the most politically explosive and technically problematic components of government today. No matter how much the Republican Party would like to end and/or privatize the program, they also realize its great utility as a sacred cow. All of these programs have at least ameliorated the most brutal effects of the economic meltdown, making life minimally bearable or sustainable for many people who would otherwise be hungry, jobless, homeless, sick, on the street—and potentially disruptive.

From this perspective, the New Deal era never quite ended. We tend to think of the heyday of liberalism ending in 1968, or 1972, or 1980, when political forces that were hostile to the welfare state gained a great deal of power and momentum, but from their own perspective their gains agains the welfare state have been relatively paltry. They lowered taxes on the rich, broke the political power of unions such as PATCO and the Teamsters through anti-labor policies and deregulation, and ended Aid to Families with Dependent Children in 1996. Many of the liberal policies of the 1930s and 1960s remain in place, helping to sustain the ordinary function of society and cushion some of the worst blows of the recession. That we are in a moment when the political zeitgeist seems to have turned toward dismantling many of these government programs that make life minimally sustainable for the poor and unfortunate is frightening, but their durability should give some cause for hope—greater hope than one would feel after reading the prodigious liberal historiography of New Deal decline.

Indeed, we might look at the New Deal as merely a response to a uniquely catastrophic crisis, but such a perspective assumes that such crises are genuinely unique and exceptional—i.e., that capitalist democracy trends toward an equilbrium, and only a truly exceptional event could throw American political culture off its normal course. The economic crises of today (and likely tomorrow) suggest otherwise. We may be in another New Deal moment—though, as the students in my class suggest, the current emergency remains poorly understood and inadequately addressed, even by the critics of the status quo.

This is why the Occupy movement has been so important. The Depression was not just breadlines spooling out from soup kitchens; it was also workers engaging in sitdown strikes, disrupting the normal flow of production by occupying their workplaces and refusing to move. Such tactics have since been disallowed by the courts and Congress, but their militancy and physicality lent an urgency to protest that no handbill or speech could express. Occupy Wall Street/Atlanta/Charlotte/Des Moines has been a modern sitdown strike, and the legal and political authorities have taken typical steps to snuff it out. The symbolism of a contemporary tent city remains—it calls people’s attention away from Kim Kardashian’s wedding, as well as the tired explanations that pin blame for the recession on feckless homeowners. It focuses attention on problems of inequality, poverty, and injustice—where the focus ought to be, in my opinion, and where it clearly has not been for most of the time since 2008, despite the occasional flare-up of discontent toward bankers and their bonuses.

There are deeper currents of discontent and opposition, of course, and we have seen these sometimes ugly, irrational outbursts in recent years. Since Obama’s election, we have seen instances of terrifying violence: Joseph Stack flying a plane into a government building in Austin, Nidal Malik Hassan’s shooting spree at Fort Hood, an attack on the National Holocaust Museum, and Jared Loughner’s deadly assault on Congresswoman Gabriell Giffords, which claimed the lives of several other victims. Such events need not be barometers of political or economic disorder. A wave of school shootings hit the country in the mid-to-late 1990s, when unemployment was low and wages were rising for some Americans. As Lawrence Goodwyn pointed out in his classic study, The Populist Moment, most people for most of history have been poor and oppressed, yet uprisings against injustice have been relatively few and far between. Unpleasant conditions do not necessarily give rise to resistance, and prosperity does not necessarily ensure social placidity. If anything, the idea of a “revolution of rising expectations” can explain why people in a society where conditions are actually improving can imagine a better future and seek even greater social change—such a development arguably occurred throughout the Americas, Europe and Japan in the 1960s. People see that change is possible, and want more. Likewise, one might expect that widespread suffering and injustice would prompt people to riot in the streets, but social disorder has been relatively limited in the United States. The same, of course, cannot be said for Europe or the Middle East in 2011.

Political and social change is, ultimately, not a mechanical process. The past is unpredictable, as the Soviets used to say, and the future is even more so. In retrospect, the Occupy movement looks like a belated and inevitable expression of people’s frustration with an unfair system where those who wreaked havoc on the lives of millions were allowed to go free and a grinding “recovery” has failed to help many people in dire straits. But there was little that was inevitable about the men and women who endured the heat and cold, arrest and imprisonment to make their case against the inequity of the American establishment. People may very well express their rage through other channels, such as self-destructive drug or alcohol abuse or random acts of violence. Recently, a series of devastating arsons has affected Los Angeles, with the suspect's motive reportedly a "rage against Americans"; around the same time, several firebombings hit a mosque and Hindu temple in Queens, the most famously and proudly diverse borough in New York. The attacks at first appeared to be hate crimes, motivated for religious prejudice or racism or xenophobia. While the alleged perpetrator seems to have been motivated by a personal vendetta, the real story remain unclear.

At such moments, we see America burning—in much the way one would expect a society where great gaps separate the fantastically wealthy and the barely surviving, where people cannot find education or housing or healthcare at a cost that is even remotely sustainable, despite the fact that resources exist in abundance. The Great Recession may not be the Great Depression, but it has its own resistance and its own anger and its own combustible and unpredictable ingredients. The exclamation point on a long era of free markets, fear-mongering, inequality and unemployment might be the molotov cocktail that hit places of worship throughout Queens: a Starbucks frappucino bottle, lit aflame.

Alex Sayf Cummings

Sad when we the right and left can both agree on your statement,"most of the participants represented a younger generation who looked to the future with little hope for success" Pray that we address the root and stop merely pointing blame at each other.

ReplyDelete