Can you spot the Medievalist in this picture?

Chicago dogs, deep dish pizza, nasal Midwestern accents, and sunny 50 degree days. Three of these things are associated with Chicago in January. Perhaps the larger forces of the universe took sympathy on the army of academics that descended upon Chicago last week for the annual American History Association conference (one might note the annual meeting of the American Economics Association also held there conference in the Windy City last week, throttling native Chicagoans with questions about opportunity costs, endogenous influences, credit supply in the age of financial crisis and so on). The dark arts of academic employment deserved at the very least blue skies and semi-warm weather. As always, a fetid mix of desperation and hope – desperation because well the market for tenure track jobs still sucks, and hope because the conference revealed a number of insightful new scholars and ideas that promise to lead the field in the near future.

1. The 1960s and Chicago

..

MLK at Soldier's Field 1966 - Chicago Freedom Movement

Chicago ‘68: Rethinking Local Black Activism and the Battle for Urban America

.

Too often tropes about the 1960s portray the early years as a simmering cauldron of racial and ethnic egalitarian possibility only to be betrayed by the violent and ultimately disappointing rights movements of the decade’s conclusion. However, several scholars pushed backed against this characterization arguing that the late 1960s proved vital in influencing the local Black Power movement and establishing the policy arcs of the 1970s in terms of Black homeownership, community activism, police organization, and politics of space visa via museums.

Keeanga Yamahtta Taylor, "Tenant Unions, Rent Strikes, Fighting Foreclosure, and Eviction Blockades: Black Chicago’s Struggle for Housing Justice"

.

Keeanga Yamahtta Taylor illustrates how the image and reality of rat infested homes led to tenant rights organizations in Chicago’s black communities of the late 1960s. While many historians suggest Martin Luther King’s housing justice movement failed due to the machinations of Mayor Richard Daley (MLK once described opposing Daley as akin to punching a pillow) and his influence over traditional sites of Black political opposition (think Black churches and elected leadership) for Taylor, MLK’s attempts to establish housing justice proved not the culmination and throttling of a movement but rather a catalyst for a coherent and effective campaign for minority homeownership. While many have portrayed the King - Daley encounter as one that ultimately contributed to the fracturing of the civil rights movement, Taylor points out that post-King Black Chicago continued to fight for fair and equitable housing. The rise of tenant unions and similar organizations utilizing a variety of means to protest poor conditions (picketing, sit ins, rent strikes) forced many landlords to address their concerns and in several cases enabled tenants to eventually transform housing contracts into mortgages.

Erik S. Gellman, "Faith in Black Power: Chicago’s Urban Training Center for Christian Mission, 1966–70"

.

Erik Gellman explores the role of Chicago’s Urban Training Center (UTC) in creating black led organizations and activism that persisted well into the 1970s. Though started by predominantly white University of Chicago seminarians who employed the U of C lab model, the UTC soon came to be dominated by Saul Alinsky like social action. This shift coincided with a shift in leadership as increasing numbers of local, largely black residents came to the fore. The UTC’s efforts helped to connect Chicago’s geographically divided Black communities. Importantly, UTC graduates contributed to wider social movements in the city from Operation Breadbasket (led in part by UTC alum Jesse Jackson) to the Woodlawn Organization. Gellman focuses especially on the Coalition for United Community Action (CUCA), who in 1969, successfully protested for better integration in the building trades. Additionally, the UTC encouraged participants to move past simple “survival” politics focusing increasingly on economic justice and access to capital as branches of the UTC tried to establish connections between Chicago’s financiers and the city’s Black organizations, a kind of precursor to today’s LISC. The opening of numerous other similar campaigns in cities across the nation (locally as well as the aforementioned CUCA provides one example) based on the UTC model points to the importance of this organization in dialogues regarding agency and 1970s social movements.

DuSable Museum co-founder Margaret Burroughs

DuSable Museum co-founder Margaret Burroughs

Ian Rocksborough-Smith, "Chicago’s DuSable Museum of African American History in the Black Power Era: The Washington Park Relocation"

.

In his recent work Black Arts West: Culture and Struggle in Postwar Los Angeles (2011), Danny Widener delves into the role of black artists in defining twentieth century metropolitan struggles. Widener focuses especially on the role that black artists and artist organizations played in crafting aesthetic and political critiques that challenged municipal institutions and structures in the name of a broader African American working class. In a similar fashion, Ian Rocksborough Smith analyzes the role of Chicago’s DuSable Museum in “transmitting African American values” to the broader public while impacting Chicago’s “cultural physical landscapes.” The DuSable Museum created a middle class space among the wider Black Arts cultural milleu and amplified Black Chicago's place within the public sphere. Established in 1961 and originally located on South Michigan Avenue, by 1974 the Museum set up shop in Washington Park. Rocksborough Smith explores both the decades long build up among black "cultural workers" like Margaret and Charles Burroughs (the husband and wife founders of the museum) who built on the tradition of Black Chicago Renaissance of the 1930s-1950s and the struggle to successfully move the museum to a larger venue. The Burroughs and others created a vital Black cultural and intellectual life that emphasized African Americans contributions to the world and protested Chicago’s and the nation’s denial of Black history. The museum’s relocation to Washington Park – long a site of the city’s Black culture from the Bud Billiken day parade to weekend festivals and craft markets – proved more difficult than expected. A former police station, the city dragged its feet regarding the new location until a petition campaign that included esteemed journalist Vernon Jarrett and Alderman Ralph Metcalfe (himself a critical figure in Chicago’s political scene) along with local cultural actors such as the Field Museum, Art Institute, and Chicago Historical Society, forced the municipal government to relent. Selling itself as a “bootstrap public cultural resource”, museum advocates adopted a rhetoric that highlighted its commitment to Midwestern history and art and cultural practice. The Museum served as a critical “free space” in an emerging Black power movement. In the 1980s, Margaret Burroughs advised the city’s growing Mexican/Mexican American museum to create its own independent cultural space, illustrating the continuing importance of a diverse racial and ethnic presence in the public sphere.

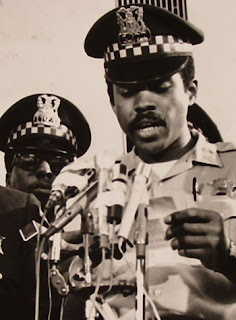

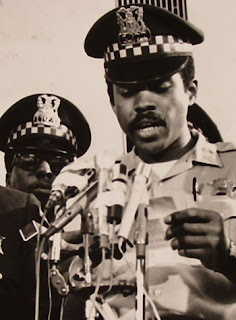

AAPL members speaking to the press circa 1968

AAPL members speaking to the press circa 1968

Megan Adams, “Beyond the Police Riot: The Politics of Chicago’s Patrolmen after 1968”

For too long, 1968 Democratic Convention and the 1969 assassinations of Chicago’s Black Panther leadership defined the CPD. To outside observers, 1968 Chicago appeared to be divided between a recalcitrant white police force, the minions of the aforementioned Mayor Daley, and a largely white left oppositional presence that erupted in violence amid the collapse of the Democratic party. UC Berkeley’s Megan Adams pushes back against this characterization pointing out that while the above events certainly remain significant, the CPD through the establishment of the Confederation of Police (1965) created an internal site of protest and cohesion. Though largely white, the Confederation eventually claimed 8000 members with a small but significant minority presence (The Confederation even elected an African American as its president in 1972) The 1968 formation of the African American Patrolman’s League (AAPL) provided another powerful means of internal protest as the Confederation and AAPL rejected their economic (no collective bargaining agreement until 1981) and political treatment (under the then newly created IID – basically Chicago’s internal affairs division – police lacked many of the rights guaranteed to criminal defendants under Miranda v. Arizona including the right to remain silent) under the monarchical Chicago mayor. The AAPL’s critiques (along with its 1975 lawsuit against the Federal Treasury for providing funding to Daley that the AAPL argued encouraged segregation within the CPD) led to increased minority representation within the department as 1976’s graduating class consisted of the largest proportion of non-white offices in Chicago history. The affirmative action program established within the CPD would later be emulated in cities like NY, Detroit, and Seattle. Reminiscent in some ways of Edward Conlon’s 2004 work Blue Blood (admittedly not an academic work), the Harvard educated New York City police officer depicted a force whose internal workings operated in numerous political directions including dissent. Moreover, Conlon suggested the perception of the NYPD’s fealty to Rudolph Guliani proved false as many officers believed Guliani had reneged on promises regarding economic issues. Likewise, Adam’s work gets at the complexity of municipal workers as both symbols of and political actors within cities, especially those living in the hot house environment of the late 1960s.

2. Not Your Parent’s Reconstruction

.

Reconstruction - Part of a larger, longer more troubling story

Reconstruction - Part of a larger, longer more troubling story

Expanding the Boundaries: Putting American Reconstruction in National and Transnational Terms

.

For the past two decades or so, transnationalism has proven a powerful lens for re-evaluating established historical epochs. Under this rubric, the idea of an established American post-Civil War federal power no longer seems so obvious as ethnic and labor tensions in northern cities, conflicts with Native Americans in the expanding West, and a resentful and violent Southern resistance to Reconstruction suggests a nation very aware of its weaknesses and less sure of its power and stability. Operating in large part in dialogue with the work of Elliot West, Nancy Bercaw, Gregory Downs, and Carole Emberton reconfigure Reconstruction and Western expansion as two parts of a larger process of national transformation that reflected the broad economic and political anxieties afflicting American citizens. (In addition, one might suggest, as commentator Stephen Kantrowitz did, that gender and worries about masculinity in the face of western expansion and rapid industrialization deserve some attention here.) The panel’s presenters remind audience members of works by Rebecca Edwards, Nancy Cott, Alison Sneider, and Amy Kaplan while employing theoretical frameworks of Michael Foucault (especially in regard to the importance and influence of discourse and the political role of bodies/remains) and Tony Bennett among others.

Celebrating or commodifying Modoc leader Captain Jack?

Carole Emberton, "The Other Panic of 1873: Federal Authority in the South and West"

Drawing on the aforementioned West and Amy Kaplan’s influential work, The Anarchy of Empire, Carole Emberton looks to reconfigure how historians think about Southern Reconstruction and Western expansion. Instead of viewing them as distinct and unrelated processes, Emberton encourages historians to consider them as two pieces of the larger project of national expansion and transformation. Focusing on the importance and meaning of two events: 1) the assassination of American General Edward R. S. Camby at the hands of the Native American Modac tribe and 2) the massacre of 100 freemen miltia members at the hands of the white supremacist White League of Colfax, LA, Emberton suggests that each represented justifications for US imperial reach in the South and West. The racial logic upholding both events illustrated a complex nexus of race, federal power, and citizenship. For example, many Southerners viewed the occupation of the South by federal forces as hypocritical since the government refused or failed to achieve any sort of equivalent occupation of Native American lands by the military. Open resistance by Native Americans, in the minds of some Southern observers, deserved federal retribution making federal occupation of the South an even greater insult. Emberton juxtaposes this example with efforts by the Colfax White League and the federal government in part to illustrate that in each case, the established narrative argued that white actors had attempted to negotiate peace with recalcitrant actors, whose violence in the face of such negotiations justified state and vigilante violence. This in turn, supported America’s late nineteenth century imperial ambitions that by 1898 supported occupation in the Philippines and elsewhere under the rubric of American tutelage.

Americans' imagined Mexico was as colorful as this map in the 1870s

Gregory P. Downs, "The Mexicanization of American Politics: The Transnational Reconstruction of Authority in the Postbellum United States"

.

Like Emberton, recent Choice Book award recipient Gregory P. Downs argues rather than putting to rest questions of federal stability, the decades following the Civil War represent a national government struggling to address crisis in Northern cities, pacify Native Americans on the Western frontier (notably the defeat of US troops at the Battle of Little Bighorn), and impose federal authority over the rebellious South. Critical postbellum American observers characterized US political fortunes with comparisons to an imagined Mexico defined simultaneously by tyranny and anarchy. However, Mexicanization’s meaning depended largely on context and political interest. When debating federal occupation of the South, Southern critics pointed to the tyranny of French intervention in Mexico (non-democratic monarchical rule) as a corollary to federal occupation of the South under Reconstruction. In other moments, the inability to completely end Native American uprisings in the West and the actions of paramilitaries like the KKK or the various White Leagues that developed across the South pointed to the anarchy of imagined Mexico in the United States (some observers ironically argued that Porfirio Diaz’s overthrow of Huerta served as example of Mexico’s instability, which is not well … accurate). In order to promote their own interests, Democrats and Republicans alike utilized the rhetoric of Mexicanization. This relationship moved in both directions as some Mexican liberals professed an alliance or brotherhood with the US justifying Mexican limitations on rights in the context of Reconstruction.

The Army Medical Museum circa twentieth century

The Army Medical Museum circa twentieth century

Nancy Bercaw, "Human Remains and the Measure of Freedom: Military Medicine and the Reconstruction of Race in the Post-Emancipation United States"

.

Arguably the most theoretical of the three papers, Bercaw's piece draws upon theories by Foucault, Tony Bennett, and one might suggest Ann Stoler, to explore how governmental display of Native American and African American remains prove illustrative of larger issues regarding race, citizenship, and federal power. From 1867 – 1898 the army (via the Army Medical Museum established in 1862) collected over 23,000 Native and African American remains, thus, creating a racialized archive that removed the humanity of the individual, thus relegating them to the role of specimens used as evidence of American racial order in an age of an insecure federal power and burgeoning imperial hopes. Curators displayed Native American skulls as proof of a vanishing “pure race” that could be reduced to a racial taxonomy. In contrast, African Americans, newly emancipated had been, at least in theory, given citizenship. As the United States’ first non-white citizenry, the museum displayed the organs of dead freedmen and women but did not identify them by race. African American skulls were not included suggesting that though still perniciously discriminated against, the government refused to display the skulls of its own citizens. Conversely, Native American skulls, offered “a visual archive of a dying race.” An assuring notion for a nation that as already copiously noted struggled to quell Native American resistance while adjusting to the legal inclusion of African Americans (Bercaw argues that one of the museum’s leaders displaced his discomfort over the newly inducted citizens by projecting his anxiety onto Native Americans, a people “rejecting U.S. power”) Like Ariela Gross in What Blood Won’t Tell or 2006's Ann Stoler edited collection Haunted by Empire, Bercaws’s talk engaged ideas regarding the expansion of citizenship whether within its borders or at its imperial edges. Bercaw's insights further our understanding of American racial policy that has long been messy, no less so than during the tumultuous years of the postbellum nineteenth century.

3. The Modular Military?

|

| Here, there, everywhere! |

Everyday Soldiers: The Limits of Militarization in Postwar American Society

In recent years, historians and social scientists like Michael Sherry, Ann Markusen, Beth Bailey, Jennifer Light, Roger Lotchin, and Caroline Lutz among others have reflected on the place, role, and influence of the military on domestic civilian life, national and regional economies, and its relationship to citizenship. The increasing public private nature of military expenditures led Eisenhower to famously warn America of the nefarious military industrial complex while C. Wright Mills provided an early definition in The Power Elite. Still, the idea of the military often evokes thoughts of an unstoppable bulging force. Instead, the Everyday Soldiers panel suggests that militarization assumes a more adaptive or as one commentator noted “modular” nature, capable in some forms of near invisibility, making it arguably an even more insidious presence. (To once again paraphrase The Usual Suspects, “The greatest trick the devil ever performed was convincing the world he didn’t exist” – yes T of M likes to gender the devil.)

[Editor’s note: The presence of a long haired Walter Sobchak in the audience made Everyday Soldiers the “it” panel of the AHA.]

UMT recruits praying for some excitement

UMT recruits praying for some excitement

Amy Rutenberg, "Failure at Fort Knox: Public Opinion and the End of Universal Military Training"

As the military moved into the immediate postwar era, atomic age fears envisioned that the next war would prove “sudden, large, and deadly”. For some military and government officials, this meant America’s male population needed to be broadly prepared for rapid military conflict. However, public ambivalence about a “garrison state” (notably in the shadow of Nazi and Soviet totalitarianism) limited the scope and vision of official plans. Though part of larger War Department plans spanning back to WWI, after a legislative push in 1944, the government instituted an experimental trial program at Fort Knox. In "Failure at Fort Knox", Reutenberg examines the publicity arising from this experimental program illustrating public ambivalence and the limits encountered by the military even in this trial effort. From the outset, the Fort Knox experiment faced opposition from a broad array of groups. Many Americans viewed the military as the improper place for the cultivation and transference of moral and civic values. Critics argued that churches, schools and families proved better conduits for such ideals. Emphasizing physical health, good hygiene, and other middle class virtues, the Fort Knox program consciously avoided strict regimentation (it offered GED classes, a swimming pool, and other accoutrements of middle income life). Participants “responded as individuals and developed as individuals”, no doubt to reinforce at the least the idea of a democratic America (for example, rather than the usual forms of discipline in the military the Fort Knox UMT employed a demerit system and had a trainee court.) Unfortunately, the government failed to ever explain why this sort of preparedness proved so vital and why the military should be the institution to install moral and civic values rather than civic and religious groups. Additionally, media portrayals depicted this service much like the Boy Scouts, thus engendering skepticism and resentment among veterans and others. Even worse, the military's own brochure stressed the program as more a right of passage than a plank in national security.

Short answer? Yes. PCYF Ad

Short answer? Yes. PCYF Ad

Rachel Louise Moran, "The Advisory State: Physical Fitness through the Ad Council, 1955–65"

When in an episode of Mad Men, the scurrilous Roger Sterling suffers a heart attack, the cynical ad executive mutters to the paramedics, “All these years I thought it would be the ulcer. I did everything they told me, I drank the cream, ate the butter. Then I get hit with a coronary.” Mid-1950s America looked pretty unhealthy from a modern day perspective, but as regrettable as we view dietary habits and physical fortitude of the nation’s citizenry in the 1950s and 1960s now, Americans of that era shared similar fears regarding their own children. Impending invasion and large scale war, all necessitated a physically fit population. Rachel Louise Moral suggests that this fear served as proxy for larger worries about America as a “nation of weaklings” thus inspiring Eisenhower to establish the President’s Committee on Youth Fitness (led, for a time by everyone’s favorite Republican Tricky Dick Nixon) which worked with state and local organizations to help coordinate on issues regarding the physical fitness of the nation’s youth. Though it helped to coordinate efforts, the PCYF did not fun state or local efforts. Established under Eisenhower, the PCYF (later known as the President’s Committee on Physical Fitness – PCPF) expanded significantly under JFK. Through public private partnerships and alliance with the Advertising Council (the AC – which today is known for producing PSA’s like McGruff the Crime Dog and Smokey the Bear) the PCYF/PCPF recorded profits but failed to make any significant improvement in the physical health of the nation’s youth. Celebrity endorsements, corporate partnerships (Kodak, Diet Rite were early participants), and the Ad Council’s guidance – all at nearly no cost – greatly improved promotion. PCPF publications and the legendary “Chicken Fat” recording (which sold over 100,000 copies in its first year) helped to put the council in the black. If the council failed to improve the actual health of Americans, it did contribute to the establishment of state and local fitness councils and also points to the increasing neoliberal approach regarding government presence in American lives.

.

Maybe this isn't so new...

Maybe this isn't so new...

Joy Rohde, "The Rise of the Contract State: Privatizing Social Science for National Security"

In From Warfare to Welfare: Defense Intellectuals and Urban Problems, Jennifer Light examines how military experts influenced urban policy and thinking in the post war era. In this way, Cold War technological innovations and beliefs came to shape urban development. Trinity University’s Joy Rohde performs a similar service by highlighting the place of social scientists working for Cold War national security councils in late twentieth century and their effect on military conflicts and urban population control. Though 1960s activists rightly critiqued the university/military partnerships of the period, eventually forcing the military off college campuses, they in no way ended the prevalence or influence of these military intellectual think tanks. Instead, away from the gaze of critics or the rigor of academia, the Pentagon and federal government established research institutes like the Special Operations Regional Office (SORO) or the Instituted for Defense Analysis. Not only did research institutes like SORO continue their research, they expanded their purview into civilian life, thus, further militarizing the nation. Population control and domestic security became new focuses. Here Rohde reinforces ideas put forth by Jeremy Suri in Power and Protest. Suri argued that during the Cold War, China, the USSR, France, and the US all shifted their national security attentions domestically to squashing internal dissent. Rohde provides more evidence of this while also pointing out the privatization of militarization identifying the same neoliberal force that culminated in private militia’s like Blackwater. Moreover, much as Light suggests, Rohde illustrates how this public private nexus of social science experts later morphed into a revolving door of intellectuals passing in and out of government offices, later using their connections to gain contracts and establish private security firms creating a veritable security state embedded in various sites around the D.C. Beltway.

4. Rocking the Cold War

.

Punking Ronnie

Punking Ronnie

Cold War Kids: The Ideologies of Punk in the East and the West

.

What would a T of M account of an academic conference be without a panel on the importance of music and culture? Cold War Kids addressed this pathological need. Not to be confused with the similarly titled band (think the song “Hospital Beds”), panelists explored the intersection between punk, politics, race, and Cold War attitudes. Though none of the panelists formally referenced works by Birmingham School writers like Dick Hebdige and to a lesser extent Paul Gilroy, Gilroy and Hebdige’s spirit inhabited the panel like Sid Vicious at a Sex Pistols Reunion tour.

The Weirdos and nuclear annihilation

.

The Weirdos and nuclear annihilation

.

M. Montgomery Wolf, “'I Keep Thinking of World War III': American Punks Rock against Reagan"

.

Throughout 1998’s SLC Punk!, main characters Stevo (Matthew Lilliard) and Heroin Bob (Michael Goorjian) rail against Salt Lake City’s conservative Mormon culture while denigrating the presidency of Ronald Reagan. SLC Punk! serves as useful analog to M. Montgomery Wolf’s examination of 1980s (mostly West Coast) American punks like LA’s Weirdos, the Adolescents, the Circle Jerks, and of course, legendary San Pedro outfit The Minutemen (Michael Azzerad’s excellent Our Band Could Be Your Life contains a great chapter on the Minutemen along with others on Fugazi, the Replacements, Minor Threat, Big Black, and so on). While early punk cohorts eschewed political statements (though one could argue the Clash, though obviously not American, might represent an exception to this rule), this “second cohort” though not formally aligned politically, expressed dismay at Reagan’s simultaneous sunny optimism (remember “Morning in America: Prouder, Stronger, Better”) and apocalyptic nuclear vision (S.D.I. and the constant threat/rhetoric of nuclear annihilation). In “Paranoid Chant,” the Minutemen find it hard to carry out the day’s tasks without returning to the paralyzing fear of nuclear war and WWIII. Cultural productions like “The Day After” (still the highest rated TV movies of all time), in which small town Kansas dealt with the aftermath of nuclear engagement, only heightened this incongruous tension between yuppie individualistic positivism and the dark reality of atomic age existence. Perhaps D. Boon expresses it perfectly in “Paranoid Chant," “I try to work but all think about is WWII … I don’t worry about crime anymore/so many frightened faces/I keep thinking of Russia/Paranoia scared shitless!”

Hating Mitterand, Communism, and immigrants

Hating Mitterand, Communism, and immigrants

Jonathyne W. Briggs, "Force de Frappe: Rock against Communism in Socialist France"

.

If American punks reacted to Reagan’s domestic and foreign policy doctrine with absurdist bursts of music critiquing the burgeoning New Right warrior, conservative skinhead French punks responded by creating their own sense of community. Still, as Indiana University’s Jonathyne W. Briggs points out, the kind of community they established focused on fascist racist right wing leanings that opposed what they saw as creeping communist and multicultural influence. For a emerging group of racist skinheads, the Mitterand administration, the Common Program (an agreement between France's socialist and communist parties to basically get along), communism and immigration threatened French identity. Conservative newspaper Le Figaro summarized the fears of punk/skinhead bands like Tolbiac’s Toads, Kontingent 88's or SK when it labeled the new French government a “Marxist Collection.” Instead, French punks emulated the working class white supremacist strain of punk known as Oi! to promote a confused nationalist vision of France that opposed the multiculturalism of Mitterand’s administration while appropriating Nazi symbolism as a means to assert a new French identity and create a “third space” between capitalism and communism. Not even Le Pen’s National Front went so far as to utilize Nazism in their definition of the French body politic. If Mitterand wanted to assimilate France’s Arab and North African populations, band’s like Tolbiac’s Toads wanted the nation to eliminate them and encouraged violence against communists and immigrants alike. If many French citizens viewed the French Revolution ambivalently or even as a national catastrophe, for these skins it proved essential to French identity as one prominent skin commented, “Robiespierre was a true skin.” Apparently, the revolution’s contribution to the creation of socialism in the 1800s escaped many skinheads. Though the feared Marxist take over never occurred – the Common Program agreement collapsed in 1985 – the movement of French skins reveals simmering cultural tensions within 1980s France and signposted future issues regarding immigration and French identity that bedeviled France in the 1990s and 2000s.

Brygada Kryzys - offending Polish sensibilities everywhere

Brygada Kryzys - offending Polish sensibilities everywhere

Raymond Patton, "The Struggle over Punk in Communist Poland: Notes on Deconstructing 'The Alternative'"

When is style political even when it’s not meant to be? In his 2009 publication, The Power of the Zoot, Luis Alvarez illustrates how Zoot suit subculture, its interracial nature, sexuality and style, formed opposition and in some moments, unwitting assistance to American WWII policies. Though hardly overtly political, the style, dress, demographics, and sexuality of the subculture threatened American domestic normatives regarding race, gender/sexuality, and consumerism (though as Alvarez points out it, it also drew many Zoots into the wartime economy that ultimately supported the very war effort and culture they opposed). Though no organization or spokepersons emerged, in part through style the subculture garnered negative attention by many white Americans and authorities (witness the Zoot Suit Riots in Los Angeles) Similarly, drawing on Stuart Hall (regarding his theories about how the struggle for culture creates political constructions and identities) and one might assume the aforementioned Hebdige (notably the work Subculture: The Meaning of Style), Drury University’s Raymond Patton illustrates how Poland’s punks in the 1980s ignored the kind of direct political stances that their peers in France and America came to embrace, yet ended up occupying a political space visa via their expression of style. Opposing political institutions in Poland – Solidarity and the Communist Party (CP)- attempted to co-opt the movement only to be horrified by the style and music of punks like Clinical Death and Brygada Kryzys (translated Crisis Brigade). The explosive popularity of punk with Polish borders and its apparent critique of communism attracted the attention of Solidarity who initially tried to incorporate the aforementioned Brygada Kryzys but found their musical stylings (both in sound and appearance) to be in conflict with Solidarity’s vision of Polishness. Yet, the subversiveness that turned off Solidarity stemmed not from political stances but ideas about Polish identity and style. In the case of the CP, punk’s place in culture symbolized a larger rift within the party between reform and Stalinist retrenchment. Clearly, Stalinists rejected songs like “Radioactive Block” by Brygada Kryzgs (which according to Patton when translated consists of seven words mostly having to do with concrete, which as the presenter accurately noted probably was a brilliant distillation of Warsaw’s built environment under communist rule) while reformists believed that the movement provided a bridge between the party and the new youthful generation so deeply invested in punk. In this way, Solidarity and Stalinists (religious organizations like the Forum for Catholic Though looked none too fondly on Polish punk as well), political opponents in most contexts, shared similar fears regarding punk’s influence (one CP official labeled it “electrification plus epilepsy”). Unfortunately, as in most stories of subcultures the success (can one say commodification?) of punk in Poland also meant the very bands performing lost control of the medium’s message.

5. Other Notable Papers

Ben Coates, "Transnational Legal Networks and the Limits of American Power, 1906–39"

.

T of M alum Ben Coates looked at the Institut de Droit International, or Institute of International Law, a network of lawyers from Europe, the US, and Latin America that was active in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Founded in 1873, the Institute saw itself as "the legal consciousness of the civilized world”—it brought together advocates of international law from a variety of nations, each bringing the distinct perspective of his or her own political culture to the broader project of establishing some of kind of institutions to enforce international norms. English lawyers cited case law; the French, sociology; and Germans sought to reconcile international law with their own philosophic and political tradition of the ideal state. Advocates of international law hoped to create a system that encompassed and reconciled the national law of individual countries. Coates observes that their goal was riven by contradiction: why would “international law” need to be “internationalized”? The group’s meetings brought together lawyers in the hope that they would produce a better, more scientific system by exposing legal practitioners to counterparts with a wide range of perspectives. (The group even institutes quotas for various countries to ensure diverse attendance—at least to a degree.) These international lawyers remained proud of their own national legal traditions despite being “wary of nationalism in the abstract,” Coates says.

The strength of international law in the era before World War I was its practicality, its closeness to politics and policy, but this pragmatism could also be a weakness. International lawyers hoped to create a system that accommodated national differences while enforcing some broad legal norms through some mechanism or another, but the their visions for international law reflected their individual national orientations. American law professor James Brown Scott, for instance, argued for a global system based on his own country’s experience, without quite realizing that the evolution of the United States was in many ways unique and not universally applicable. Scott suggested the US was an international entity itself, a federation of colonies or states that voluntarily accepted federal coordination. He did not want a world central government, but proposed an international body similar to the US Supreme Court that could adjudicate disputes among the states. Americans generally accept the authority of the Court without it needing to enforce its decisions; it holds power by virtue of public opinion and acceptance. To pursue his American-centric vision of international governance, Scott lobbied to increase number of american members. Almost all international lawyers agreed on some kind of adjudication of disputes, but not on the form of the institution. Eschewing Scott’s view, many other international lawyers wanted a more vigorous form of regulation; the creation of the League of Nations after WWI represented the more legislative, democratic kind of world government that Scott opposed. Scott promoted a Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Nations -- echoing, of course, echoed the Declaration of Independence, but endorsing only broad guidelines such as the right to exist as a state and the right to sovereignty over territory. The Institute ultimately failed to embrace his plan, and American political culture continued on its isolationist course in the 1920s. It would take more than two decades and another world war for a new system of international governance to take shape under American leadership.

Yael Sternhell, "Constructing the Enemy’s Past: The Federal Archives Bureau and the Road to Sectional Reconciliation"

.

Sternhell, an assistant professor at Tel Aviv University, discussed the fascinating saga of how federal archivists attempted to tell the story of the American Civil War in the 1870s, working with and sometimes against the Southerners who possessed records of the Confederate government. The archivists’ initial goal, Sternhell says, was “preserving the enemy’s past” so future generations would remember “southern sins and northern virtues.” As commentator W. Fitzhugh Brundage pointed out, government record-keeping in the nineteenth century was generally abysmal; in one particularly tragicomic case, Tennessee’s state government used its own records for kindling, happy with their pragmatic use of useless paper to generate heat and save money. In this case, though, the narrative about the conflict written by the Federal Archives Bureau would help to shape public understandings of the war for years to come—part of the larger process of regional reconciliation analyzed by David Blight and other historians.

Sternhell points out that Southerners were reluctant to part with the documents early in the 1870s, but later on even Confederate diehards like Jubal Early realized the value of turning over records when the federal government was prepared good money for them. The 1878 appointment of a Confederate general Marcus Wright as the Archives’ agent in the South also prompted Southerners to be more cooperative. Meanwhile, Sternhell notes tiny linguistics shifts in writings by federal archivists that seem to signal a changing perspective about the war; earlier on the Southerners were referred to as “rebels,” but over time the word Confederates came into more frequent, while federal workers gradually dropped the quotation marks around “Confederate States” and stopped using the word “so-called” as often. The implication seems to be that they increasingly took seriously the reality of a Confederate state during the war, rather than the earlier view of the Confederacy as a mere rebellion within the United States.

As Southerners and Northerners increasingly collaborated on the federal government’s Official Report on the war, a curious outcome resulted: the Report incorporated Confederate documents and Southern perspectives to tell a much less damning story about the war. The resulting document offered a seemingly “neutral,” fact-based accounting of the events of the war, Sternhell argues, which offered little sense of guilt, causation, or accountability. “The work of managing the confederate records and preparing them for publication… created a documentary basis for the brothers’ war narrative that would shape the nation for decades to come,” she says. The story of the Federal Archives Bureau and its documentary work on the Civil War offers an interesting and little-known chapter in the bigger story of postwar reconciliation and, indeed, the evolution of historical and documentary practices in the United States.

Jay Gould, strangling commerce and the press with telegraph wires

Richard R. John, "'For the Benefit of the Whole Human Race': The Significance, Memory, and Legacy of the Postal Telegraphy Movement in the Nineteenth Century United States"

.

A historian who writes on the telegraph, telephone, and postal service, John has been making the case for years that traditional business history fundamentally misunderstands the role of government in shaping and sustaining private enterprise. In this paper, he argues that conventional wisdom gets it wrong by supposing that innovative business comes first, and government regulation only comes along after the fact to stifle and constrain the activities of private citizens. The story of the telegraph is often view as demonstrating Americans’ fundamental preference for leaving communications in private hands, unlike, say, the heavy involvement of the British government in broadcasting (the BBC) or France’s state control of the telegraph. Historians often assume that inventor Samuel F.B. Morse’s effort to get the federal government to buy his patents and operate the nation’s telegraph network for the public good was a hopeless fool’s errand. However, as John suggests, public ownership of the telegraph remained a live issue throughout the mid-to-late nineteenth century. The presumption that Americans always lean toward privatizing such infrastructure is merely the result of an ideological victory, in which defenders of big business established the virtue of “private enterprise” (a term that John argues came into wide use during the battle over Western Union’s telegraph monopoly). In fact, he pointed out, by far the biggest government agency in the nineteenth century was the postal service, the nation’s premier communication medium, and the Government Printing Office was the biggest publisher of printed material during the same period.

Historians have unfortunately forgotten or overlooked the postal telegraphy movement of the 1860s and 1870s, which sought to incorporate the nation’s telegraph system into the Post Office by buying out private operators (chiefly Western Union). Attendees at the AHA panel were likely surprised to learn that Ulysses S. Grant supported the idea and a law even passed in 1866 that would allow the federal government to buy up the telegraph lines. Grant’s postmaster general, John A.J. Creswell, believed that people have a right to “the best and cheapest means of communication and intercourse; no one had the right to extort the public by monopolizing a force of nature,” just like light and air. Creswell’s words reflect a view that was common in nineteenth century America, which held that the government should foster and even subsidize the freest possible circulation of information within the republic; the Post Office was not, as we assume today, a business that ought to run a profit. As Paul Starr and others have pointed out, American policy promoted publishing and communication by establishing the postal service and subsidizing the press by providing favorable rates for newspapers (what we now know as “media mail”). Public ownership of the telegraph would have fit into this same policy framework.

As John’s paper made clear, though, the idea of postal telegraphy foundered in the face of machinations by Western Union and the speculator Jay Gould in the 1870s and 1880s. Americans at the time waged a lively effort to fight monopoly amid a widespread recognition of the threat posed by concentrated economic power, but some began to doubt the value of anti-monopoly legislation. If anything, some economists argued, such measures paradoxically strengthened

the position of financiers like Gould, who bought and sold industries like it was all a big game. Appalled by the venality of Gould and the callousness of Vanderbilt (who infamously said, “The public be damned!” when asked about the impact of his business’s actions), later businessmen learned to burnish the image of private enterprise. They adopted an ethic of public service—most notably Theodore Vail, who justified AT&T’s “natural monopoly” of the phone system by claiming to be committed to a higher motive than profit. At any rate, the war over control of the telegraph and what it meant for American political culture is a fascinating one, and one hopes that it will become part of a broader history of anti-monopoly thought in the US.

.

You'd have to be crazy not to like this guy

Yana Skorobogatov, "'The Higher Circles': The Western Intellectual Community and the Campaign for Human Rights in the USSR, 1968–84"

.

Skorobogatov, a PhD student at the University of Texas, revealed an untold chapter in the history of both Western relations with the Soviet Union and the human rights movement. Focusing on “intellectuals as nonstate actors,” Skorobogatov looks at how members of the intelligentsia in the US and Europe tried to develop a coalition with Soviet dissidents to defend the rights of persecuted intellectuals in the détente era. In the process, NGOs (non-governmental organizations) and professional organizations in the sciences and academia set transnational values above national identity. Their efforts ran up against predictable resistance from Soviet authorities, who cited a 1932 act banning voluntary organizations as a pretext for suppressing human rights activism among scientists and other scholars. In response, dissidents argued that they were more like a group of co-authors than a formal organization.

Skorobogatov explained how Western scientists were haunted by the memory of corrupt and abusive science under the Nazis and sought to prevent the same abuses from occurring in the Soviet Union. They also identified with their counterparts in the USSR, who were increasingly accused of mental illnesses such as schizophrenia in order to incarcerate them under gruesome conditions and silence their dissent. (Such a maneuver avoided the need for a show trial and successfully impugned the integrity of the deviant scholar by discrediting their most valuable quality—intellect.) When one accused individual cited the Soviet Constitution to defend his right of free speech, one judge responded with incredulity. “Who takes Soviet laws seriously?” he said. “You are living in an unreal world.” (Enough said.) In response to such abuses, Western scholars decided to employ their “intellectual capital” as a weapon, Skorobogatov said, refusing to participate in or lend their own prestige to important scientific conferences in the Soviet Union. The efficacy of this tactic is hard to determine on the basis of the talk alone, and at least one audience member raised the question of whether Western scientists worked hard only to defend their “own kind,” as opposed to the many ordinary Soviet citizens who suffered oppression. In any case, though, this talk offered an intriguing window into the politics of science, international organizations, and human rights, as well as the internal tensions of détente itself.