The first and most iconic R.E.M. record of all, “Radio Free Europe,” came at a time when the music industry was in turmoil, in 1981. The long boom of record sales began to flag in the late 1970s, amid grinding recession and the transition of the baby boomer demographic into adulthood. The brief efflorescence of punk proved to be a momentary and luckless fad for the music industry, which soon moved onto smoother and poppier offerings, leaving punk to evolve into the niche subculture it has been more or less ever since. MTV was just emerging on the horizon. Its earliest hit declared, “Video killed the radio star,” but R.E.M. had different thoughts on the matter. “Decide yourself if radio’s gonna stay,” Michael Stipe insisted on the Georgia band’s first single.

The lyrics of “Radio Free Europe” paint an impressionistic view of the world of 1981, when the fate of music remains in question and the Cold War world itself is in transition. It evokes an image of mobility and change – “straight off the boat, where to go?” – familiar to both the immigrant and the Southerner who first goes “abroad,” beyond the bounds of the former Confederacy. Equal parts New Wave spunk and Sixties psychedelic pop, with a touch of jagged punk spirit, the song seemed to be an anthem for the possibilities of independent music and the power of media to open up a new world. The incessant refrain of the song is “Decide yourself.”

Kudzu is a social construct

I was reluctant to write anything about the recent demise of R.E.M., despite the fact that they were one of the bands nearest and dearest to my heart since I was thirteen years old. This reluctance derives in part from the flood of glowing encomia that have issued from Salon, Slate, and so many other media outlets in the last few weeks. R.E.M. “invented alternative rock.” They led a music revolution. They were, we are told, the greatest American rock band of the last thirty years. In other words, they still find themselves mired in second place after U2 for world’s greatest/most gigantic/longest-lived band of recent decades -- an honor most other big bands were either too self-destructive or idiosyncratic to hold. Long ago, a drunken Edge told an interviewer that if U2 were the Beatles, R.E.M. were the Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young of their day. Whatever the merits of CSNY, it is hard to say that is “Judy Blue Eyes" was more influential than “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds." I don’t think that backhanded compliment ever stopped stinging. When I first heard the news R.E.M. was breaking up, I was disappointed. They seemed to be in the middle of a late-career renaissance akin to Bob Dylan’s remarkable run from Time Out of Mind to Modern Times, and the declaration seemed to come out of nowhere – ending very much with a whimper. R.E.M. had previously pledged to break up if any member left the band (they didn’t), and rumor had it they would part ways in the year 2000 (ditto). Now they decided to break up for no apparent reason, in the wake of a solid and fairly well-received record, 2011’s Collapse into Now. As Louie C.K. says, no one ever gets divorced at just the right time.

Given the outpouring of respect and love for the band since their breakup, though, it seems like a shrewd move. Like an artist whose works shoot up in value after his death, the band’s premeditated demise has prompted people to recognize their immense contribution to music of the indie, college, southern, and general “modern” or “alternative” rock varieties.

The R.E.M. century: dune buggies, pink feather boas, and Jimmy Dean

I hope this sudden departure from the scene will lead critics and other listeners to discover the charms of underappreciated albums like New Adventures in Hi-fi, the epically dour follow-up to Monster that inaugurated the band’s slide into commercial oblivion, thanks in no small part to the near-suicidal choice of stream-of-consciousness ramble “E-Bow the Letter” as a first single. I hope Accelerate will get a second look, as well as the handful of terrific songs from Reveal and Collapse into Now.

The R.E.M. story is an invaluable one for the recent cultural history of pop music. With less militance than, say, Fugazi, and less angst than Pearl Jam or Nirvana, they grappled with the problem of translating independent music for a large audience, in an age when big rock bands with near-universal appeal became increasingly scarce, even extinct. It is the story of a band marrying a grab bag of disparate influences – the chiming Byrds guitars, the guttural, ragged baritone that Michael Stipe stole from Patti Smith, the lyrics that blended psychedelia, Southern Gothic and punk poetry – into a uniquely regional variant, plying their craft in the independent circuit for years before managing the transition to the mainstream success and megamillion record deals, and still finding a way to experiment and put out smart, thoughtful, adventurous music even when it meant sacrificing their mainstream popularity.

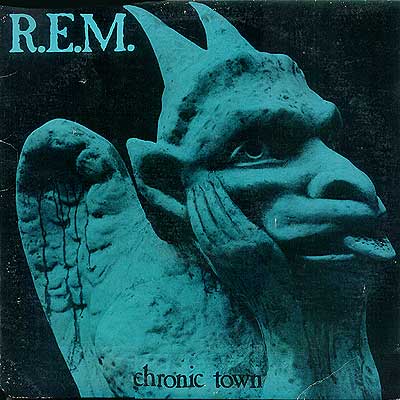

The wonderful mystery and ambiguity of early records like Chronic Town, Murmur, and Reckoning was never to be recaptured, but that was all thirty years ago. What the band continued to represent, in spite of their missteps and mainstream popularity, was the possibility that the South might have a different face – a few arty guys from Georgia, with a penchant for punk and ambivalent sexuality, a fact that was crucially important for “Southern boys just like you and me,” as Steve Malkmus once put it – and rock could remain open to the eccentric and obscure, while working within a familiar template of melody, harmony, and noise that appealed to a wide range of listeners.

R.E.M. departs the stage at a moment when the music industry is again in crisis, just as when they arrived. The question of whether radio’s gonna stay – whether it can still “polish up the gray” – is uncertain, between the many competing and uncertain experiments in internet and satellite radio, streaming services like Pandora and Spotify, the revival of vinyl, and so forth. Rather like the Great Depression, when broadcast radio seemed to offer free music to all and poverty threatened the record industry with annihilation, we are in a moment of transit and anxiety – just what R.E.M. captured so aptly with “Radio Free Europe” thirty years ago. We can hope, perhaps, that another band will appear before long to capture the uneasy vicissitudes of this moment and write music that shows yet another way forward.

Alex Sayf Cummings

No comments:

Post a Comment