Tweedy’s being pissy because he doesn’t want to play any Black Eyed Peas songs. What the fuck? People love that shit.

Not saying they’re a good band – they’re fucking terrible – but if you want people with money to give that shit away, play the Black Eyed Peas.

But no Tweedy’s pulling this fucking “I’m in Wilco, so I’m going to play Wilco songs” bullshit, like he knows anything about fundraising.

So it goes without fucking saying that he’s going out there and playing “I Gotta Feeling” right fucking now.

Also, would it fucking kill this motherfucker to smile every now and then? Cheer up, Tweedy!

-- from Dan Sinker, The F***ing Epic Twitter Quest of @MayorEmanuel, p. 135

When Dan Sinker incorporated Rahm Emanuel’s favorite band into a faux-twitter feed he had set up for the future mayor, few observers would have expected Jeff Tweedy to actually perform the cheesy pop songs mentioned in the tweets. At a release party for Sinker’s Twitter opus (and TofM can’t recommend the book highly enough as a satire of both politics and the power of media to shape political narratives), Tweedy arrived guitar in hand and performed his rendition of “I Gotta Feeling,” as well as a spoken word version of “My Humps.”

That Tweedy could poke fun at himself might seem surprising to those who attended pre-2003 Wilco shows or saw the excellent documentary, I Am Trying to Break Your Heart. At a late 1999 show at New York City’s Roseland Ballroom, Tweedy appeared disaffected, selecting Wilco’s best dirges for the occasion, casting a dark pall over the show. In the documentary, infighting with former bandmate Jay Bennett left Tweedy irritable and anxious. He seemed a man beset by industry intrigue and battling over the direction of the band. When, after a brief creative skirmish with Bennett, Tweedy announces, “I think I’m going to go throw up,” the viewer simply thinks he’s being hyperbolic. Of course, then he actually throws up, telling the camera that he was hospitalized several times for this kind of thing as a child. Long story short, Tweedy and his bandmates seemed far from happy.

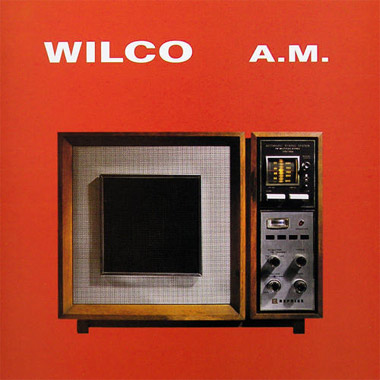

Yet, in many ways, Wilco’s evolution from 1995’s A.M. to the recently released The Whole Love seem to parallel American consciousness in pre and post 9/11 period. Wilco themselves matured from their early status as minor-league spinoff of the legendary alt-country group Uncle Tupelo. Though gifted with a tangy-sweet voice and a knack for catchy songs, Tweedy generally played a spry sort of sub-McCartney to the brooding genius of his Tupelo bandmate Jay Farrar. Soon enough, Farrar’s post-Tupelo band Son Volt blew up with the grungy-country hit “Drowned,” and few expected that great things lay ahead for Tweedy’s own project, Wilco. A.M.’s charms were little appreciated at the time, though the sprawling follow-up project, Being There, a double album that stretched to encompass white noise, bluegrass, classic country balladry, and crunchy power pop, prompted critics to take a second measure of Tweedy’s abilities.

Wilco continued to expand its range with the Beatlesque orchestral pop of Summerteeth and the gauzey, ramshackle brilliance of Yankee Hotel Foxtrot, both of which seemed not only to move forward musically but also emotionally. Each new album combined the band’s keen melodic instinct to a widening repertoire of textures and instrumentation, even as their lyrics increasingly centered on themes of despair, violence, and self-loathing. Yet by Wilco’s last album, the formerly depressive Tweedy seemed downright jubilant. The title track of the self-titled Wilco even meditated on the darker parts of the band’s catalog, albeit with a knowing smile:

Are you under the impression this isn't your life?

Do you dabble in depression?

Is someone twisting a knife in your back?

Are you being attacked?

Oh, this is a fact that you need to know

Oh, oh, oh, oh

Wilco, Wilco, Wilco will you love you baby

So how did Wilco become so cheerful and reliable? How does a band once seemingly consumed by the darker sides of life emerge in a post 9/11 America as a beacon of good cheer? After all, at their New Year's Eve show in 2004 at Madison Square Garden, Tweedy came on stage in pajamas, taking their encore to cover songs like “Breaking the Law” by Judas Priest.

Tracking the meaning of Wilco’s career means more than chronicling the many moods of its lead singer. In fact, the band provide a valuable window into the vast number of technological and political changes that unfolded over the past decade. Technologically, Wilco embraced the Internet, even streaming its controversial Yankee Hotel Foxtrot album months before its release. Politically, Wilco seemed to draw strength from its opposition to Bush. At a October 2004 show at Radio City Music Hall, Wilco ended the concert with a plea to the crowd, as Tweedy begged the NYC audience, “Don’t be controlled by fear” – followed by the band ripping into “Shouldn’t Be Ashamed,” a none too subtle dig at the administration at the time.

First, the Music

.

Released two years prior to 9/11, Summerteeth served as “Jeff Tweedy's statement of purpose,” according to one critic. Though the characterization seems laughable today, the album did strike observers at the time as a major artistic leap for the still-unproven band. Drenched in pop that many likened to Pet Sounds and Revolver, the pop leanings of Summerteeth masked a dark interior. As Pitchfork reviewer Neil Liebermann noted, “Undermining this sticky-sweet pop party in a delicious irony, and ultimately supplying Summerteeth with its depth and success, is Tweedy's dark contemplation.” The album’s narrator proves unreliable as he struggles to deal with a failed relationship, balancing images of domestic violence, jealously, and anger with moments of elation and optimism. Much like pre-9/11 America, the surface layers appeared perfectly healthy, but dig a bit deeper and trouble was brewing. Perhaps no two songs best represent this dichotomy than the tracks “Via Chicago” and “ELT.” Lieberman says it best:

"The new Wilco is so good it's like fucking a thousand puppies in the mouth"

Tracking the meaning of Wilco’s career means more than chronicling the many moods of its lead singer. In fact, the band provide a valuable window into the vast number of technological and political changes that unfolded over the past decade. Technologically, Wilco embraced the Internet, even streaming its controversial Yankee Hotel Foxtrot album months before its release. Politically, Wilco seemed to draw strength from its opposition to Bush. At a October 2004 show at Radio City Music Hall, Wilco ended the concert with a plea to the crowd, as Tweedy begged the NYC audience, “Don’t be controlled by fear” – followed by the band ripping into “Shouldn’t Be Ashamed,” a none too subtle dig at the administration at the time.

First, the Music

.

Released two years prior to 9/11, Summerteeth served as “Jeff Tweedy's statement of purpose,” according to one critic. Though the characterization seems laughable today, the album did strike observers at the time as a major artistic leap for the still-unproven band. Drenched in pop that many likened to Pet Sounds and Revolver, the pop leanings of Summerteeth masked a dark interior. As Pitchfork reviewer Neil Liebermann noted, “Undermining this sticky-sweet pop party in a delicious irony, and ultimately supplying Summerteeth with its depth and success, is Tweedy's dark contemplation.” The album’s narrator proves unreliable as he struggles to deal with a failed relationship, balancing images of domestic violence, jealously, and anger with moments of elation and optimism. Much like pre-9/11 America, the surface layers appeared perfectly healthy, but dig a bit deeper and trouble was brewing. Perhaps no two songs best represent this dichotomy than the tracks “Via Chicago” and “ELT.” Lieberman says it best:

The album's confusion climaxes during its keystone, the majestic "Via Chicago", and its counterpart "ELT". On the former, a scorned lover stews, "I dreamed about killing you again last night/ And it felt alright with me." Then, a couplet of unsettling stream-of-consciousness lyrics give way to Tweedy as he tears into a disturbingly deliberate, off-key guitar riff that might very well be the musical moment of 1999. Interestingly, the celebratory "ELT" finds our sad psychopath repented and healed: "Oh, what have I been missing/ Wishing, wishing that you were dead." Taken on its merits, the song is almost unimaginatively sincere, but in context, it becomes enigmatic. As the narrator shuffles his story for our approval, which spin are we to believe? Brilliantly, the album leaves such questions unanswered.

The contrasts between such radically different emotions laid the groundwork for Yankee Hotel Foxtrot soon after, an album that’s far removed from the orchestral pop of Summerteeth. Shrouded in ambient clicks, beeps, and hisses, YHF seemed the perfect post 9/11 album: hazy, anxious, and reflective. When Tweedy sings “I would like to salute/The ashes of American flags/And all the fallen leaves/Filling up shopping bags” at the conclusion of “The Ashes of American Flags,” it felt like a remorseful summation of our lives: patriotic consumerism in the face of terrorism. The fact that Wilco recorded YHF before 9/11 made the album that much more eerie. On “Poor Places,” Tweedy describes a recent beating that has left at least one man in poor shape, bandaged and emasculated, “His jaw's been broken/His bandage is wrapped too tight/His fangs have been pulled” and yet a sense of hope seems to filter through, as he follows this bleak portrayal with “And I really want to see you tonight.” Yet, Wilco saved perhaps the most resonant lyrics for “Jesus, Etc.,” where “Tall buildings shake/Voices escape singing sad sad songs/ Tuned to chords /Strung down your cheeks/Bitter melodies turning your orbit around.”

The reception of YHF might have been quite different if not for the controversy and hoopla that surrounded its release. Major label Reprise refused to release the album, claiming that its ambient textures were too weird and experimental to sell in the pop marketplace. Such claims perplexed many fans once the album was released by label Nonesuch (ironically, a smaller subsidiary of the same company that owned Reprise); apart from a brief period when “Outta Mind Outta Site” played on modern rock radio in 1996, Wilco had never been a radio band, and YHF actually contained some of the poppiest and most melodic songs in the band’s catalog, such as “Jesus, Etc.” and “Heavy Metal Drummer.” The kerfuffle over the album, though, postponed its release until April 2002, even though the songs had been written and recorded in late 2000 and early 2001. When Americans finally heard about the tall buildings shaking, the ashes of the flags, the wounds of 9/11 were still raw and very fresh in their memories. It was comforting to reminisce about “the innocence I’ve known, playing Kiss covers, beautiful and stoned” as the war party dragged America into its catastrophic response to the terror attacks during the Spring of 2002.

As the band pushed forward, they released A Ghost is Born, Sky Blue Sky, and Wilco (the Album), each on Nonesuch. Though on A Ghost is Born, the haze of YHF remains, the album offers glimpses of youthful hope in songs like “Spiders (Kidsmoke)” and the self parody of “Late Greats” (The best band will never get signed/K-Settes starring Butcher's Blind/Are so good, you won't ever know/They never even played a show/You can't hear 'em on the radio). With many observers looking to see how the band would expand the experimental gestures of YHF, these albums seemed to indicate a contentment with their existing sonic palette – or at least a steady scaling back of any arty ambitions. Ghost contained the widest divergence between poppy singalongs and epic, extended song structures, while Sky Blue Sky – Tweedy’s first release after his battle with painkillers – was scorned by some critics for its easy-going, 70s rock vibe. The subsequent self-titled album included country-rock stompers of the Being There variety, like “You Never Know,” although “Bull Black Nova” offered an intriguing excursion into dense, oppressive dissonance.

Mostly, the band seemed content to enjoy its new independence from major labels and drug addiction, pursuing a reliable middle path of country-inflected indie rock. At the same time, though, the depression and anxiety that haunted Ghost Is Born melted away over time – a result of Tweedy’s overcoming addiction, no doubt, but also of the changing mood of American life. Ghost was recorded in late 2003 and early 2004, when the US was definitively enmeshed in its Iraq disaster and the nation was heading toward a grinding election battle between irreconcilable political forces. By 2007, when Sky Blue Sky was released, the darkest depths of the Bush years seemed behind us, although the collapse of the subprime market that undermined the entire economy was just beginning. The sunnier Wilco came out in 2009, reflecting both the sorrows of the recent past ( “Country Disappeared”) as well as a flinty determination to survive in the face of continual crisis (“You and I,” “Wilco (the Song)”). “Every generation thinks it’s the worst,” Tweedy sang, “thinks it’s the end of the world.” After the war on terror, two endless wars in Asia, and the near-total destruction of the world financial system, Americans could be forgiven for thinking the apocalypse was upon them.

Learning to Live with the End of the World

.

Wilco’s discography certainly parallels the changing fortunes of America around the turn of the twentieth century, but it also tells an interesting story about the fall and rise of the music industry during the same period. On one level, they represent a familiar story about major labels picking up subcultural movements and packaging them for broader consumption. Uncle Tupelo won fame for popularizing a return to American roots music in the late 1980s, a conscious reaction of slick Nashville country and the pop mainstream in general that came to be known as “No Depression” (after the 1936 Carter Family tune that the band covered on a 1990 album of the same name). As Tweedy recently admitted, Tupelo “hated everything that wasn’t a field recording from Appalachia, anything that wasn’t raw and amateur-sounding,” and the band refused to seek mainstream success, quitting at the height of its influence, shortly after the release of the 1993 classic Anodyne. Tweedy and Jay Farrar went their separate ways, and Farrar’s Son Volt became an unexpected (albeit short-lived) sensation amid the mid-90s gold rush of alternative, grunge, post-grunge, and indie rock. Wilco had even less success on commercial radio, but the steady rise of its reputation among critics through the late 1990s ensured a devoted following.

That following was not devoted enough for Reprise Records not to shed the band for its unruly, slightly arty ways in 2001, at a time when the mainstream industry was still lurching to respond to the threat of online file-sharing, and many labels were dropping indie-leaning artists from their rosters that had outlived their usefulness. Bands like Luna and Wilco commanded a tiny but consistent market share; the major labels, though, saw little advantage to keeping them around as record sales continued to slide in the aftermath of Napster, 9/11, and the recession of the early 2000s. AOL’s controversial 2001 takeover of Time Warner resulted in the Internet giant ordering the latter to clean house at its record division, cutting six hundred jobs. Supporters of Wilco were among those cut, though the efforts at shoring up Time Warner’s music business accomplished little in the long-run. And the whole saga offered a preview of the problems that would beset the new megacorporate behemoth; after all, the company gave itself a PR black eye by rejecting and postponing Wilco’s album only to have one of its own subsidiaries, Nonesuch, sign on with the band shortly after.

The story captures not just the suicidal tendencies of the mainstream record industry – the YHF episode also exemplified the new ways music would be distributed in the years to come. Tweedy had originally hoped to release the album on September 11th, 2001, of all days, but the label confusion set the date back. As leaked versions circulated on the Internet, the band took the nearly unprecedented leap of streaming the entire album on its website, beginning September 18th. (Two years earlier, Tom Petty had run into trouble with his label just for posting an mp3 of his new single, “Free Girl Now,” online, which over a hundred thousand fans promptly downloaded.) As Greg Kot observes in his book Ripped, the band’s site received huge traffic and, on the subsequent tour, fans were seen singing along to songs from an album that had not even been properly released yet. All of us have witnessed the stony stares of the faces of concertgoers who wait through a new song the band is trying out live for the first time, unable to relate with the music because it was unfamiliar. Wilco’s decision to “give away” the music (in a sense) likely bolstered the success of their tour, which may not have generated as much interest if fans had no access to YHF.

Wilco has continued to offer new music as streams and downloads on its website, NPR, and other forums, while Tweedy has voiced support for file-sharing. “I look it as a library,” he said in 2005. “I look at it as our version of radio” – an outlet for artists who do not have the marketing or mainstream backing to get on Clear Channel-controlled broadcasting. The band recently took the final leap by setting up its own label, a tactic that artists have favored from the Beatles to Black Flag and Ani Difranco, but which is perhaps more viable than ever with electronic distribution. Indeed, they follow in the footsteps of Radiohead, who famously gave their 2007 album In Rainbows away on an NPR-like donation model (also known as “for free”) and continue to chart their own label-less course.

Critics have pondered whether such a go-it-alone strategy can work for bands who do not already possess the loyal fan-base and name recognition that Wilco and Radiohead enjoy, and the question remains open. What is beyond question is that Wilco’s path from the highly likable, alt-country non-geniuses of 1995 to the zeitgeist-defining art rockers of 2002 to the beloved independent institution of today encapsulates much of what has happened in American life and music over the last decade or two. Tweedy and his compatriots were there for both the No Depression and alternative music bonanzas of the early 1990s, and they survived the music industry crunch of the early twenty first century by chronicling America’s larger sojourn from disaster to disaster. They came out on the other side with a body of work most recently topped off by The Whole Love, an album that seems to encompass many of the styles and moods that marked their career. Its first single, “I Might,” muses on the frustrations of parenthood (“you won’t set the kids on fire, oh, but I might”). More telling is the b-side – a cover of Nick Lowe’s sardonic 1977 track “I Love My Label” – released, of course, by the band’s very own dBpm.

.

Yankee Hotel Foxtrot (2001-2)

The reception of YHF might have been quite different if not for the controversy and hoopla that surrounded its release. Major label Reprise refused to release the album, claiming that its ambient textures were too weird and experimental to sell in the pop marketplace. Such claims perplexed many fans once the album was released by label Nonesuch (ironically, a smaller subsidiary of the same company that owned Reprise); apart from a brief period when “Outta Mind Outta Site” played on modern rock radio in 1996, Wilco had never been a radio band, and YHF actually contained some of the poppiest and most melodic songs in the band’s catalog, such as “Jesus, Etc.” and “Heavy Metal Drummer.” The kerfuffle over the album, though, postponed its release until April 2002, even though the songs had been written and recorded in late 2000 and early 2001. When Americans finally heard about the tall buildings shaking, the ashes of the flags, the wounds of 9/11 were still raw and very fresh in their memories. It was comforting to reminisce about “the innocence I’ve known, playing Kiss covers, beautiful and stoned” as the war party dragged America into its catastrophic response to the terror attacks during the Spring of 2002.

As the band pushed forward, they released A Ghost is Born, Sky Blue Sky, and Wilco (the Album), each on Nonesuch. Though on A Ghost is Born, the haze of YHF remains, the album offers glimpses of youthful hope in songs like “Spiders (Kidsmoke)” and the self parody of “Late Greats” (The best band will never get signed/K-Settes starring Butcher's Blind/Are so good, you won't ever know/They never even played a show/You can't hear 'em on the radio). With many observers looking to see how the band would expand the experimental gestures of YHF, these albums seemed to indicate a contentment with their existing sonic palette – or at least a steady scaling back of any arty ambitions. Ghost contained the widest divergence between poppy singalongs and epic, extended song structures, while Sky Blue Sky – Tweedy’s first release after his battle with painkillers – was scorned by some critics for its easy-going, 70s rock vibe. The subsequent self-titled album included country-rock stompers of the Being There variety, like “You Never Know,” although “Bull Black Nova” offered an intriguing excursion into dense, oppressive dissonance.

Mostly, the band seemed content to enjoy its new independence from major labels and drug addiction, pursuing a reliable middle path of country-inflected indie rock. At the same time, though, the depression and anxiety that haunted Ghost Is Born melted away over time – a result of Tweedy’s overcoming addiction, no doubt, but also of the changing mood of American life. Ghost was recorded in late 2003 and early 2004, when the US was definitively enmeshed in its Iraq disaster and the nation was heading toward a grinding election battle between irreconcilable political forces. By 2007, when Sky Blue Sky was released, the darkest depths of the Bush years seemed behind us, although the collapse of the subprime market that undermined the entire economy was just beginning. The sunnier Wilco came out in 2009, reflecting both the sorrows of the recent past ( “Country Disappeared”) as well as a flinty determination to survive in the face of continual crisis (“You and I,” “Wilco (the Song)”). “Every generation thinks it’s the worst,” Tweedy sang, “thinks it’s the end of the world.” After the war on terror, two endless wars in Asia, and the near-total destruction of the world financial system, Americans could be forgiven for thinking the apocalypse was upon them.

Learning to Live with the End of the World

.

Wilco’s discography certainly parallels the changing fortunes of America around the turn of the twentieth century, but it also tells an interesting story about the fall and rise of the music industry during the same period. On one level, they represent a familiar story about major labels picking up subcultural movements and packaging them for broader consumption. Uncle Tupelo won fame for popularizing a return to American roots music in the late 1980s, a conscious reaction of slick Nashville country and the pop mainstream in general that came to be known as “No Depression” (after the 1936 Carter Family tune that the band covered on a 1990 album of the same name). As Tweedy recently admitted, Tupelo “hated everything that wasn’t a field recording from Appalachia, anything that wasn’t raw and amateur-sounding,” and the band refused to seek mainstream success, quitting at the height of its influence, shortly after the release of the 1993 classic Anodyne. Tweedy and Jay Farrar went their separate ways, and Farrar’s Son Volt became an unexpected (albeit short-lived) sensation amid the mid-90s gold rush of alternative, grunge, post-grunge, and indie rock. Wilco had even less success on commercial radio, but the steady rise of its reputation among critics through the late 1990s ensured a devoted following.

Uncle Tupelo (left to right): Farrar, Tweedy, and another guy

That following was not devoted enough for Reprise Records not to shed the band for its unruly, slightly arty ways in 2001, at a time when the mainstream industry was still lurching to respond to the threat of online file-sharing, and many labels were dropping indie-leaning artists from their rosters that had outlived their usefulness. Bands like Luna and Wilco commanded a tiny but consistent market share; the major labels, though, saw little advantage to keeping them around as record sales continued to slide in the aftermath of Napster, 9/11, and the recession of the early 2000s. AOL’s controversial 2001 takeover of Time Warner resulted in the Internet giant ordering the latter to clean house at its record division, cutting six hundred jobs. Supporters of Wilco were among those cut, though the efforts at shoring up Time Warner’s music business accomplished little in the long-run. And the whole saga offered a preview of the problems that would beset the new megacorporate behemoth; after all, the company gave itself a PR black eye by rejecting and postponing Wilco’s album only to have one of its own subsidiaries, Nonesuch, sign on with the band shortly after.

The story captures not just the suicidal tendencies of the mainstream record industry – the YHF episode also exemplified the new ways music would be distributed in the years to come. Tweedy had originally hoped to release the album on September 11th, 2001, of all days, but the label confusion set the date back. As leaked versions circulated on the Internet, the band took the nearly unprecedented leap of streaming the entire album on its website, beginning September 18th. (Two years earlier, Tom Petty had run into trouble with his label just for posting an mp3 of his new single, “Free Girl Now,” online, which over a hundred thousand fans promptly downloaded.) As Greg Kot observes in his book Ripped, the band’s site received huge traffic and, on the subsequent tour, fans were seen singing along to songs from an album that had not even been properly released yet. All of us have witnessed the stony stares of the faces of concertgoers who wait through a new song the band is trying out live for the first time, unable to relate with the music because it was unfamiliar. Wilco’s decision to “give away” the music (in a sense) likely bolstered the success of their tour, which may not have generated as much interest if fans had no access to YHF.

Wilco has continued to offer new music as streams and downloads on its website, NPR, and other forums, while Tweedy has voiced support for file-sharing. “I look it as a library,” he said in 2005. “I look at it as our version of radio” – an outlet for artists who do not have the marketing or mainstream backing to get on Clear Channel-controlled broadcasting. The band recently took the final leap by setting up its own label, a tactic that artists have favored from the Beatles to Black Flag and Ani Difranco, but which is perhaps more viable than ever with electronic distribution. Indeed, they follow in the footsteps of Radiohead, who famously gave their 2007 album In Rainbows away on an NPR-like donation model (also known as “for free”) and continue to chart their own label-less course.

Critics have pondered whether such a go-it-alone strategy can work for bands who do not already possess the loyal fan-base and name recognition that Wilco and Radiohead enjoy, and the question remains open. What is beyond question is that Wilco’s path from the highly likable, alt-country non-geniuses of 1995 to the zeitgeist-defining art rockers of 2002 to the beloved independent institution of today encapsulates much of what has happened in American life and music over the last decade or two. Tweedy and his compatriots were there for both the No Depression and alternative music bonanzas of the early 1990s, and they survived the music industry crunch of the early twenty first century by chronicling America’s larger sojourn from disaster to disaster. They came out on the other side with a body of work most recently topped off by The Whole Love, an album that seems to encompass many of the styles and moods that marked their career. Its first single, “I Might,” muses on the frustrations of parenthood (“you won’t set the kids on fire, oh, but I might”). More telling is the b-side – a cover of Nick Lowe’s sardonic 1977 track “I Love My Label” – released, of course, by the band’s very own dBpm.

.

So when Dan Sinker incorporated Wilco into his @MayorEmanuel feed, it seemed appropriate. Emanuel’s election as mayor ushered in a new age for a city long dominated by machines, Irish pols, and the indomitable Daleys. Like Wilco, which was rejected by the record industry behemoth, Emanuel found himself and his campaign on the outs when rival candidates challenged his residency status. (The lawsuit was later overturned by the Illinois State Supreme Court -- an entity that, like Chicago’s city government, is beyond reproach). Yet, in part through new media like Sinker’s Twitter feed, and the strength of Emanuel’s personality, the former Obama confidant emerged victorious, much like Wilco several years earlier. That new media like Twitter subsumed a former neo-folkie/alt-country militant like Tweedy no longer seemed so surprising considering Wilco’s own turn to technology – both in terms of distribution and the enigmatic, electronic haze of YHF, Ghost Is Born, and The Whole Love. Sinker’s feed expressed pathos, rage, resistance and humor, the very components that have made Wilco so resonant for the past seventeen years. With The Whole Love, it’s like Wilco’s back in the kitchen again, cooking up something special -- maybe not YHF special but special nonetheless. Or, as @MayorEmanuel put it, “Jeff Tweedy showed up with a giant plate of motherfucking brownies. Game on, bitches.”

No comments:

Post a Comment